Recorded: October 1972

Producer: George Martin

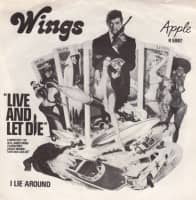

Released: 1 June 1973 (UK), 18 June 1973 (US)

Available on:

Wingspan: Hits And History

Wings Over America

Tripping The Live Fantastic

Paul Is Live

Back In The World

Back In The US

Good Evening New York City

Twin Freaks

One Hand Clapping

Personnel

Paul McCartney: vocals, piano

Linda McCartney: backing vocals, keyboards

Denny Laine: bass guitar, backing vocals

Henry McCullough: guitar

Denny Seiwell: drums

Written for the 1973 James Bond film of the same name, ‘Live And Let Die’ became one of Paul McCartney and Wings’ most successful singles.

‘Live And Let Die’ was recorded at London’s AIR Studios in October 1972 while Wings were completing the Red Rose Speedway album, and was produced by George Martin.

I read the Live And Let Die book in one day, started writing it that evening and carried on the next day and finished it by the next evening … I sat down at the piano, worked something out and then got in touch with George Martin, who produced it with us. Linda wrote the middle reggae bit of the song. We rehearsed it as a band, recorded it and then left it up to him.

The song was commissioned especially for the eighth James Bond film. John Barry, who had scored previous Bond outings, was unavailable to work on Live And Let Die so the film’s producers, Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, asked McCartney to write the theme song. McCartney had previously been asked to write the theme for 1971’s Diamonds Are Forever, but it failed to happen.

George Martin was also hired to write the score for the Live And Let Die film, and McCartney instinctively knew that he was the right arranger and producer to bring the theme song’s cinematic scope to life.

I wouldn’t have liked it if my music was going to replace John Barry’s, that great James Bond theme. I know I’d miss that. I go to see him turn round and fire down the gun barrel. Our bit comes after he’s done that and after the three killings at the beginning. I’m good at writing to order with things like that. I’d like to write jingles really, I’m pretty fair at that, a craftsman. It keeps me a bit tight, like writing to a deadline, knowing I’ve got two minutes three seconds with a definitive story theme.

The producers had intended for another performer to record McCartney’s song. McCartney and Martin, however, had other ideas. They recorded a full studio version at George Martin’s AIR Studios in London in a single day, recorded in a handful of takes simultaneously with the orchestra. Martin then took it to the Caribbean location where filming was taking place.

The film producers found a record player. After the record had finished they said to George, ‘That’s great, a wonderful demo. Now when are you going to make the real track, and who shall we get to sing it?’ And George said, ‘What? This is the real track!’

Assuming the McCartney recording was a mere demo, Harry Saltzman allegedly proposed that Thelma Houston should record the song. Once the producers accepted Martin’s insistence that it was strong enough to use, it was incorporated into the film. Another recording, by Brenda J Arnau, also appears in the film’s soundtrack.

The release

‘Live And Let Die’ was released in the UK on 1 June 1973 as Apple R 5987. It spent 14 weeks on the single chart, peaking at number nine.

In the US it was issued on 18 June 1973 as Apple 1863, and topped two of the three main singles charts.

I didn’t rate it too much alongside some of the Bond themes that had gone before, like those for From Russia With Love or Goldfinger, which are very Bondian. I wasn’t sure whether mine was, whether it would hold up with such classics, but a lot of people have put it on their list of top Bond songs. Then, when it was released, it became the most successful Bond theme so far and was nominated for an Oscar for Best Original Song – ‘When you got a job to do/You got to do it well.’

The Lyrics: 1956 To The Present

The b-side of ‘Live And Let Die’ was ‘I Lie Around’, written by Paul McCartney but sung by Denny Laine. The song was a Ram outtake completed during the Red Rose Speedway sessions. It was Laine’s only lead vocal on a Wings single.

Although Wings’ early releases had received mixed critical and commercial responses, ‘Live And Let Die’ established the band as a potent force, able to compete against rock’s premier league of performers. Although they subsequently underwent personnel changes, by the end of 1973 Wings had released Band On The Run, their most commercially successful album.

‘Live And Let Die’ is the only song to have appeared on each of Paul McCartney’s live albums, with the exception of the television recording Unplugged (The Official Bootleg).

It’s still a big show tune for us to this day. We have pyrotechnics, and the thing I think I like most about it is that we know the explosion’s about to happen, that first big explosion. Often I look at the people, particularly in the front row, who are blithely going along, ‘Live and let…’ BOOM! It’s great to watch them; they’re shocked.One night I noticed a very old woman in the front row, and I thought, ‘Oh s**t, we’re going to kill her.’ But there was no stopping, I couldn’t stop the song and say, ‘Cover your ears, love!’ So when it came to that line, I looked away. ‘Live and let…’ BOOM! And I looked back at her, and she hadn’t died after all. She was grinning from ear to ear and loving it.

The Lyrics: 1956 To The Present

Where can I find photos from the Royal World Charity Premier of Live & Let Die, July 5, 1973, at The Odeon Theatre, Leicester Square?

In the new book “The McCartney Legacy,” authors Adrian Sinclair and Allan Kozinn dispute McCartney and Martin’s oft-told tale that the producers were not planning to have McCartney sing on the soundtrack. The idea was always to have two versions of the song in the film: one by Paul and one performed by a Black artist in a nightclub scene (the original suggestion was The Fifth Dimension). They quote from the original contract to back up this statement.

When the producers asked who should sing it, they must have been asking about the nightclub scene. Martin said that they were reluctant to use Paul because Bond films had never had a male sing the theme, but this is incorrect. Louis Armstrong sang “We Have All the Time in the World,” from “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service” (the title song from that film was an instrumental).

It seems that Martin misunderstood the producers’ question and then the story was embellished as it was told and retold. Yet another Beatle myth.

I’m not sure this disproves any “myth”. To be fair, I haven’t read the book, but I read The Guardian article, and all the quotes I’ve seen are ambiguous. The smoking gun – Ron Kass’s communication to Harry Salztman – is not the actual contract. What is the date of that communication?

The “proof” includes statements such as: “seems like”, “pretty definitively”, “certainly would have” and assumptions.