Producer: John Fraser

Released: 7 October 1991 (UK), 22 October 1991 (US)

Personnel

Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, Sally Burgess, Jerry Hadley, Willard White: vocals

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir

Choristers of Liverpool Cathedral

Carl Davis: conductor

Malcolm Stewart: solo violin

Ian Balmain: solo trumpet

Timothy Walden: solo cello

Anna Cooper: cor anglais

Tracklisting

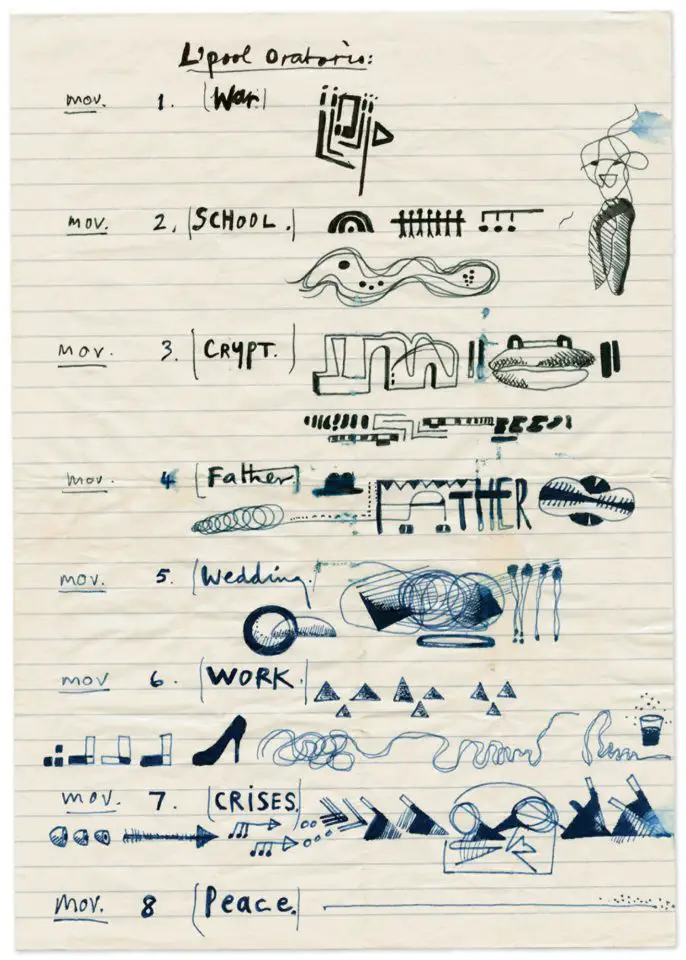

Movement I – War

Movement II – School

Movement III – Crypt

Movement IV – Father

Movement V – Wedding

Movement VI – Work

Movement VII – Crises

Movement VIII – Peace

Liverpool Oratorio, Paul McCartney’s first major foray into the world of classical music was an ambitious semi-autobiographical work in eight movements.

It was commissioned by the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, and three years later had its premiere to coincide with the orchestra’s 150th anniversary. McCartney composed the work with conductor Carl Davis, who received joint billing in the album credits.

For years I have been flirting with classical music. On ‘Yesterday’ I had a string quartet and on ‘Eleanor Rigby’ we had used string players so I always enjoyed the experience. And, in the back of my mind, there was always this thought that if I ever get a great offer to do something big in the classical world, I’d leap at it. So, the Liverpool people rang up and asked me to do this for their 150th anniversary. So it was my hometown orchestra, it was to be performed in the cathedral, which is right next door to the school where I did all my schooling and it was in an area of a million great memories for me. I always had the idea that I might do this one day so I just leapt at the offer and said, ‘OK, in two years’ time we’ll deliver. Carl Davis and myself will deliver something that you can celebrate your 150th anniversary with.’

Back in 1988 Paul and Linda McCartney had made a guest appearance in the BBC television comedy Bread, which was filmed and set in Liverpool’s Dingle area. Their minor roles in one episode, which was shown on 30 October that year, came about through Linda’s friendship with writer Carla Lane.

In the show, Jean Boht played Nellie, the matriarch of the central Boswell family. Boht was married to Carl Davis, and the two couples struck up an enduring friendship. When McCartney received the commission from the Liverpool Philharmonic, it was natural for him and Davis to collaborate.

McCartney enthusiastically embraced the chance to work in the classical tradition, settling on a full-scale oratorio using an orchestra, choir and soloists. As is the tradition, the work combined religious and secular topics, as well as drawing from his own life story.

In preparation, McCartney attended a series of classical and operatic performances. It wasn’t an entirely new field for him, however, as he had long taken an interest in classical music and instruments. Indeed, The Beatles had used them as far back as 1965, and many of his subsequent works had been scored for classical instruments.

Just as George Martin had in the 1960s provided the requisite knowledge of classical instruments that McCartney lacked, he required a foil if he was to complete the work. As well as conducting some of the world’s leading orchestras, Carl Davis had previously worked on a number of film and television scores, giving him a populist touch which was perfect for the Liverpool Oratorio.

I prefer to think of myself as a primitive, rather like the primitive cave artists who drew without training. Hopefully, the combination of Carl’s classical training and my primitivism will result in a beautiful piece of music. That was always my intention.

McCartney was used to working on brief, self-contained songs, typically working quickly in his writing and recording. Liverpool Oratorio was an attempt at a longer-form piece – as he put it, “instead of the short story, this is the novel.”

Carl would occasionally say: ‘Let me give you a little lesson,’ and, depending on what mood I was in, sometimes I would say, ‘No, Carl, we won’t do that,’ because I felt too much like a student. But occasionally if I was in a receptive mood I’d say: ‘Go on.’ And he’d say: ‘This movement is based on the rondo form.’ So I’d say: ‘What’s a rondo?’ And Carl would explain. If I was interested in it and thought it would be a good idea for us, then we would use it, which we did in the last movement: ‘Peace’ is roughly based on the rondo form. But he tried to sit me down one day with Benjamin Britten’s Young Person’s Guide To The Orchestra and I wouldn’t do it. I refused and said, ‘No, Carl, it’s too late for that, luv.’

The composers wrote the basic structure of the story one afternoon, blocking out the key movements. They then began writing the War movement, and eventually completed a first draft of the whole oratorio.

They agreed that the work should not be aimed at the crossover market, meaning that they would not rely upon pop motifs and methods in order to make it more accessible to modern audiences.

Carl Davis initially wanted McCartney to be part of the production. Dame Kiri Te Kanawa suggested he play the role of the headmaster, and some recordings exist of McCartney singing some of the parts, but in the end he did not perform.

Rehearsals with the orchestra, chorister and stand-in soloists took place on 25-27 March 1991. A test recording took place at Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral on the final day, and the pair rewrote sections and solos until it was complete.

The world premiere of Liverpool Oratorio took place on Friday 28 June 1991, in front of a capacity audience of 2,500 people at the cathedral. The 90 members of the Liverpool Philharmonic were joined by the 160-strong Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Choir, 40 choristers of the cathedral, and four world-class solo singers: Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, Sally Burgess, Jerry Hadley, and Willard White.

Just as the first performance was beginning, the lights in the cathedral went out; a single generator was being used for the recording and film equipment, causing a power overload. Thankfully, the rest of the performance continued without any unscheduled drama.

Paul at the 1991 premiere of his 'Liverpool Oratorio' in Liverpool Cathedral #ThrowbackThursday #TBT pic.twitter.com/AHocPsmaCz

— Paul McCartney (@PaulMcCartney) September 4, 2014

The 28 June performance was recorded and filmed, as was the following night’s performance. Further premieres followed in London and New York, before Liverpool Oratorio was performed around the world.

The release

A double compact disc set of the Liverpool recording was released in October 1991, to mixed reviews.

In the UK Liverpool Oratorio topped the classical chart, and reached number 36 on the main album chart.

It also topped the US classical charts, but reached only number 177 on the Billboard 200.

Initial pressings of the Japanese edition of the album came with a bonus 3″ CD featuring a six-minute interview with McCartney.

A single compact disc set, titled Paul McCartney’s Liverpool Oratorio – Highlights, was released in October 1992, and featured shortened versions of each of the movements.

Two singles were released from the album. ‘The World You’re Coming In To’/‘Tres Conejos was issued in the UK on 30 September 1991. It was followed on 25 November by ‘Save The Child’/‘The Drinking Song’, which was also issued in the US on 12 November.

Ghosts Of The Past, a documentary produced by Chips Chipperfield and directed by Geoff Wonfor and Andy Matthews, captured the process of writing and rehearsals for the oratorio. It showed McCartney and Davis composing the work, and contained footage from around Liverpool including the Liverpool Institute where McCartney had been a student.

The documentary was first shown by the BBC, and was later released on video and laserdisc.