10.31am

8 January 2015

Offline

OfflineFirstly, if you haven’t already read them, you will need to read at least the preambles to the previous monographs so I don’t have to repeat myself regarding jargon:

- John Lennon and the Lost Chord

- Paul McCartney and the Walking Talking Bass

- Ringo Starr and the Development of the Air-fill

George had the most complex development of all the Beatles. It was instrumental development, personal development, and songwriting development, in a way that managed to be related but separate to the others. He was regarded as “the quiet one” and the “Dark Horse ” by people who were intent on pigeon-holing him and disregarded his independence, skill and wit.

George grew up in public more than the others and probably the best example of that is how he surprised Paul by discussing how badly Beatlemania had affected him, because Paul had had no idea. This shows us the limits of the “one-mind” theory of the Beatles, they were after all young men who weren’t going to subject their innermost feelings to possible ridicule. He was younger but had the musical talent and the right attitude to be a Beatle, but it still meant that he was junior to The Partnership, and he was no songwriter in the beginning anyway. It was probably lucky he got some hardening to a degree before they hit the national stage. By then he had a niche of lead guitarist, harmony singer and cheeky quip to any authority. And that’s where Beatlemania kept him for an astonishingly long period even as he had completely changed.

It wasn’t simple pigeon-holing that George suffered from. They were all scarred by the pressure of their fame, but for George, a private person, it was hellish. He began to fear and hate crowds, he chafed at being trapped with the others, touring was not only exhausting but increasingly dangerous: the price was too high for him. He dug in his heels ever afterward about any resumption of touring or even public appearances. Even when as a solo artist, he could have done more touring and gigging to support his recorded output, he chose not to. He never enjoyed dealing with any press and tended to to be cautious with any person he didn’t have regular personal dealings with. I can’t blame him, he was regularly burnt by press, managers, whole organisations, the taxman. Yet throughout all this George maintained a stubborn independence and sense of humour.

But back to Beatles, George had to compete with The Partnership like a sibling, as if not being as good a songwriter wasn’t a big enough hurdle. His musical relationship with Paul in particular went from indifferent to grudging to fraught; not simply because Paul also wanted to play lead guitar but because Paul thought he always knew what he wanted in his songs and had no problem telling George and Ringo what to play. It didn’t help that Paul was often right, but we’ll never know what George might have contributed given time and a confidence-boost. When George did start writing however, Paul made every effort to help the song, while John was less interested. But the imbalance in the relationship was probably always going to be an issue, and I don’t believe George was above playing Paul and John off each other either to get his way. It’s what happens in a close-knit family, that’s the politics.

George’s influences were, for the purposes of Beatles, mainly country, rock’n’roll and Rnb/Soul. The former two he’d grown up with, the latter was later in the Hamburg days. George became the group’s authority on RnB, and he was a Chet Atkins fanboy and learnt all the licks he could. That was the kind of lead that lead guitarists did those days, straking arppegios and odd major 9ths up the fretboard. The surfer influence which lead to the so-called Mersey Beat was also strong, as no one could avoid the Shadows and the American surfer groups like the Beach Boys . The massive reverby needle-sharp guitar sound was what everyone craved. George was also a hoarder of guitars, and it’s useless for me to even try to approach any detailed chronology of his collecting except to say that he went from German hollow-bodies to American ones when he could, but probably the most important guitar was the Rickenbacker 12-string with which he really made changes to the Beatles sound. He started a lifelong passion for the ukulele later in the ’60s but the big change was going to India in 1966.

India filled a hole in George he hadn’t quite known he had. For the Beatles, it had a musical effect with George learning the difficult Indian music system and instruments, but for George it was the revelation of another way to look at the world that was far more valuable. It guided him for the rest of his life and helped him get perspective on his unique experience as a Beatle.

So I’ll break up George’s development in this fashion:

- Initial lead/harmony phase

- RnB riffing phase

- Indian phase

- Late/slide phase

It’s very simplified from other examinations like this, which is an excellent read and goes into a bit more detail about the guitars. But that’s because I have other aspects of George to cover and not merely his guitar technique. George was of course much better on technique than songwriting in the beginning, and had to learn how to string things together for himself rather than just be great at imitation. Imitation and parody is how many musicians learn songwriting and musicianship anyway, particularly the untrained ones. George was very lucky to be around two giant natural talents to learn from, it’s unlikely he would have developed as well in any other way, so being overlooked as a songwriter had its advantages.

Around the RnB phase, the Beatles songwriting changed sharply, looking for alternatives to the loose version of pop standards they had mastered, and inevitably this affected solos. Not so much removing them but radically changing what needed to be played. The Beatles never quite lost the habit for solos but it was getting very difficult to sustain. This more or less accelerated George’s songwriting efforts, he couldn’t just be the guy to play some riffs and solo and sing a bit any more, he had to become more flexible. But this took time and when he did find a new path it was practically too late for the Beatles and so most of the slide phase is post-Beatles along with some of his best songs. But don’t get the impression that it was all over for the solos. They didn’t work too well in the psychedelic era, but on the White Album George played at least 5 solos and his style had definitely changed. But let’s get to the details.

Another important thing concerns George as a lead guitarist. He started in an era where lead guitarists were there to play for the song, not the other way around, as happened far too much later on. So if I note that there’s not a solo or it’s very short or simple, I’m not criticising it, it’s there for the context of the song. Solos weren’t thought of as a major artistic statement or anything, they were added colour and a way to prevent monotony and often to restate a theme. George, like all the Beatles, contributed for the song, not for himself. That’s what made them truly great. It is very rare to get someone like a George with his extra talent as an instrumentalist and knowledge to humble himself for the song’s benefit these days.

One more note: I’m an average guitarist, and there is a great deal of nuance to George’s playing even from the start of his Beatles career which I’m not qualified to address, but I’ll try to point out good bits. I literally listen through the entire output every time I do these, and I always hear something new, particularly in the early songwriting period.

The following people thank ewe2 for this post:

Beatlebug, Starr Shine?, Dark Overlord, MarthaI'm like Necko only I'm a bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin and also everyone. Or is everyone me? Now I'm a confused bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin everyone who is definitely not @Joe. This has been true for 2016 & 2017

10.32am

8 January 2015

Offline

OfflinePlease Please Me

As we’ll see, Georges’ initial workload may not seem high compared to The Partnership, but he had worked very hard to get here. George’s chief job as lead guitarist was to sound fresh, even as he doffed his guitar at his influences. In a hit parade dominated by the Shadows, Cliff Richard and Jim Reeves, it was a big ask to bring in too much RnB and with 50 years of hindsight, it was a good move to go the rockabilly/surfer route so that the songs would be at least not too far away from commercial standards. Early Beatles period leads are often reverb-drenched stabs or cryptic squiggles of notes that fit a suggestion of style without thinking too deeply, quite appropriate for the pop machine of the day.

You can hear George doing the reverb-drenching 7th stabs and licks throughout and the solo is classic early 60’s vaguely-country reverb squiggle.

No solo, just some solid accents from George.

Anna

George gets the chief riff in the verses, notice how quiet John’s guitar is by comparison. Also, no solo!

George breaks out the 9ths, which is a hallmark of George’s job in the early days whenever the Beatles wanted something a little more exotic than 7ths.

Back to the surfer reverb stabs! That’s 3-part harmony vocals there even if it’s not obvious. I like this song and I don’t care who knows it. Bonus Paul screams for those playing at home.

George showing off his faux-jazz chops, dig those tasteful arpeggios up the chords, and the nice augmented 9ths.

Singing harmony backing and playing the key riffs, this is authentic Beatle George, right down to the chords. I still don’t know why we have two singles on this album and then they stopped doing that.

George is almost invisible here.

P.S I Love You

Invisible here too unless its George and not John doing the strumming, and doing the chord stabs instead.

George gets an odd low solo, followed by a celesta on the octave above. It’s so low it makes me think of those odd tremolo bass solos also popular in this period.

George gets his first lead to sing, and his voice, briefly separated from harmony duties, gives the song a avuncular suggestive tone, yet at the same time manages to sound plaintive and sweet. The Beatles were very good at getting away with this kind of thing.

Again showing off George’s skill and accuracy without which this cover would fall in a heap. He’s got a very sweet tone considering how limited the recording medium is at this stage, but it’s helped by the fashion for a more midrangey sound too.

Pretty straightforward chords here, nothing much for George.

Beatle George returns with the riffs and oohs! It’s not a solo so much this time as reverb chords, an interesting choice that’s stronger than a melody because it introduces the vocal build-up. And don’t forget the all-important last D 9th chord, that class that separated the Beatles from everyone else.

SINGLE: From Me To You /Thank You Girl

Notice how George’s skipping chords work in well with Paul’s bassline on the A-side, and how happy those strumming chords are on the B-side. Not the strongest of singles, but more about reinforcement of their style and attitude and a direct communication to their fans.

SINGLE: She Loves You /I’ll Get You

This is Please Please Me on steroids, there’s no better way to put it. George’s guitar is practically a commentator on every lyric, and this also became part of the style, and later a stylistic problem that George had break free from. That happy lick/sad lick is so effective and probably very tempting to repeat. The B-side is more straightforward Mersey-beat chug which we’ll be seeing a lot of now.

With The Beatles

As almost everyone realises, this is a better album even than the first, and really cements the sound. George is still Gretsch-powered, but actually gets a song of his own in here, as well as sing on a cover (poor Ringo). Nevertheless, it’s still the same formula, and it’s really the rhythms that make a difference as well as the arrangements of the covers.

The riff here is very country-influenced and the surprising ending has another exotic chord favourite E major 6. The official sheet music insists its E major 7 but shows the fingering for a 6th inversion, so as always trust your ears and caveat emptor!

George again breaks out a very country solo in this important McCartney milestone, a pleasing run of chiming octaves and thirds.

George’s first composition to make it on record, and I wish I had a dollar for all the complaints I’ve heard about it. All I can say is that John and Paul felt it was good enough, case closed. George’s relative talent at this stage should not be an issue, rather, pay attention to the influences and development of his style. The song wouldn’t be lonely among most bluesy pop efforts of the time, and the production certainly suggests that. It was a favourite gambit to have a driving verse and a relatively quiet chorus, then to up the tension in the middle-eight and have the verse follow naturally from it, all of which George accomplishes handily. Even Neil Diamond would do the same thing with Solitary Man in 1966. The song starts with the riff from the middle-eight, and the riffs (presumably John) accent off the rhythm of the melody; it appears to follow the 32-bar standard but George does a typical prickly squiggle of a solo in a verse section before repeating the middle-eight again with a final verse and a coda, so even on his first outing George breaks the rules! As for the lyrics, how typically contrarian of George to write something dismissive when every other Beatles song was Thank You Girl etc. No doubt this has ruffled enough feathers to get the equally dismissive response 😀

Acoustic lead guitar! A most unusual credit, and some very choice chords in his solo.

The Beatles follow by now a well-trodden path of RnB adaptation, with great backing vocals and the Mersey-Beat rhythm, but no solo for George.

Never mind, George gets to rock on here AND solo. He pulls out all his rockabilly stops from the introducing riff to the end.

George continues the rockabilly on this naked come-on of a song. Gosh Paul can be convincing when he wants to be.

More rockabilly and more than a bit of bluesy riffing, George sneaking in a bendy note or two among the verse riffs and and goes for it during the solo under which Paul and John have a bit of fun with the yowls and on the coda.

The mastery of this genre is a shock after the previous song, particularly from George who sounds like he could play out jazz cabaret 7 nights a week. From the strummed intervals down to the 9ths, he can schmaltz with the best.

The piano gets the solo, this time, not George.

Money

Another rouser in the same vein as Twist And Shout , although for my money (LOL) it’s more intense and spooky than the former. The power in the song actually comes from the relentless chords and the just as relentless backing vocals, and a solo here would have critically wounded it.

SINGLE: I Want To Hold Your Hand /This Boy

More Mersey-Beat fun on the A-side, which again features that rockabilly feel on the guitars with occasional stabs and bends from George, who switches to quiet arpeggieos in the B-section key-changes and note again how they opted for no solo but went for strong rhythm and vocal build-up. The B-side was an unexpected early demonstration of their 3-part harmony as well as George’s cabaret licks, but I would also hold it up as an example of where they would self-consciously parody when they were emulating a style they were not native to. See also Yer Blues .

The following people thank ewe2 for this post:

Beatlebug, MarthaI'm like Necko only I'm a bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin and also everyone. Or is everyone me? Now I'm a confused bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin everyone who is definitely not @Joe. This has been true for 2016 & 2017

10.32am

8 January 2015

Offline

OfflineA Hard Day’s Night

The songwriting is stronger and the formula is shaken up a bit. George gets another song, but also gets a new guitar to play, the famous 12-string Rickenbacker. There will be a lot of Byrds referencing going on from this point forward, but I think that it was mutual influence, and it didn’t become an obvious one until Rubber Soul . George used it pretty much on every song that I can hear.

The famous “chord”, which was really a combination of instruments. Gsus4/D says the sheet music, well ok if you say so. The ringing multiple notes of the 12-string make for difficult reading of the sheet music also, because George immediately took advantage of the instrument, as the complicated guitar tab shows. You don’t necessarily hear this subtlety but you feel it, and in combination with John’s rhythm, it’s a mini wall-of-sound that the Beatles used more than once. And we haven’t even got to the solo which is another risky tour-de-force in tandem with George Martin’s piano, which was made easier by recording at half-speed! Finally, the cherry on top, that beautiful arpeggio to fade out. Written in 20 minutes, recorded in 3 hours. They were that good.

George gets to play stabs and Dramatic Chords in the B-sections, and the characteristic octaves of the 12-string ring out in the solo which ends in a 6th.

I’m Happy Just To Dance With You

The rhythm is an odd mix of uptempo and accented chugging and it’s here we first see George’s love of putting what I think of as the “black sheep chord” into his progressions. He puts an augmented major 7th on the word “dance” in the chorus that manages to sound minor somehow. Once again he uses the riff from the middle eight as an intro, and doesn’t use a solo.

One of the common complaints about George’s early work is that the middle eights often seem forced. I can understand the criticism but would also point out how he was emulating The Partnership’s style of highly contrasting middle eights. In any case that fails here because the middle eight rolls in and out super-smoothly thank you and the minor key and rocking rhythm are a pleasing contrast that fits perfectly.

Rather than fade out, the song takes its coda from the backups and modulates that up to the Eb used in the B-sections, very tidy.

The stand-out here is George’s solo, but don’t ignore the nice arpeggios in the verses as well as the hook riff. George at times could sound almost classical in style, and this is a great example.

George plays the big chords here and you can really hear the 6ths chiming on the 12-string even when toned back a bit.

Well the Byrds comparison starts here, with that chiming Rickenbacker riff running down the scale from the 4th to the root and back up to the 2nd, practically type-casting the guitar style forever. They again match the piano and the Rickenbacker for the solo which makes a very dense combination, but I feel the piano is a bit laboured on the accents and could have been mixed back a bit, the guitar gets a bit swamped.

Surprise country song! George is forced to simplify his stabs, and not bend notes by the Rickenbacker but use ringing arpeggios and short slurs instead.

George is in Wistful Chord mode for this one, but you can still hear those chimes, if muted.

It sounds to me like George ditched the Rickenbacker for this one, the verse riffs are much more Gretsch-y.

More acoustic lead guitar from George, and a fairly straightforward job of key riff rather than solo.

SINGLE: Can’t Buy Me Love /You Can’t Do That

Released all the way back in March 1964 and bolted onto the soundtrack album released in July 1964, the A-side has George playing a wonderfully wobbly and chicken-scratchy solo on his birthday, even if you can hear the previous version at points under it. The B-side is important for the first time the 12-string got used by George and let’s not forget John’s rare lead solo! Also that chromatic coda, which still makes me laugh despite the mean lyrics.

SINGLE: I Feel Fine / She’s A Woman

The A-side would not be what it is without George’s doubled riffs on the Rickenbacker and note how he uses slurs in the solo rather than bends. This limitation of the 12-string is what would cause George to be more choosy with its use on future albums. George’s B-side contribution was the solo, clearly not on the Rickenbacker! I should have mentioned John’s contribution on this song on my piece for him, it’s great driving guitar stabs.

Beatles For Sale

From George’s point of view, this album, as countrified as it was, forced him to review using the Rickenbacker on everything, and he had to revert to a more conventional guitar, I’m not sure what he was playing by this stage, it could have been the Country Gentleman or the Tennessean depending on exactly when the former got run over. He also got given a Maton (an Australian guitar!) at this period but it’s not known if he ever used it on a recording. This album results in a reprise of earlier styles for George, and there isn’t much new here for him, so I won’t go over the old ground in songs like Baby’s In Black or Honey Don’t , fine examples of his older style that they are.

George here with an acoustic solo that’s four slurred notes! Now try to imagine the song without them. This is what I mean about the way solos were treated by the Beatles, as an all for one thing, not a “here’s my spotlight moment!” thing. It’s not always the case but in a lot of Beatles songs, Georges contribution is crucial to their flavour.

The Rickenbacker gets back in with a strong riff. Note the slurred notes again in the solo. I begin to wonder whether George’s later style would incorporate this kind of sound so he could have both the trebly chimey sound and be able to bend notes.

George tries some slidey licks in the verses (they’re very mixed back), and unleashes the full tinkly 12-string sound in the solo.

He does a similar thing in this song with a stronger riff and some stabs in the background, which adds an undeniable character to the song.

Everybody’s Trying To Be My Baby

George gets his Elvis on (or at least his Carl Perkins)! The solo is oddly restrained between playing the main riff and a couple of licks in between, and one feels he wasn’t that fussed over it.

SINGLE: Ticket To Ride /Yes It Is

The 12-string bursts out on the A-side, a riff very close to a drone in intent with its long ringing notes, but George uses a different guitar for the brief blink-and-you’ll-miss-it solo. Paul does the country lead guitar solo at the end, so its a very produced song from the guitar side of things. The B-side features George playing with a tone pedal which he’ll be doing again on a few more songs on the next album. It seems to be George trying to find a different way to slur notes and to add some variety to his sound, and opinion seems divided on the results!

Help!

Another soundtrack album but this time we’ve got the taste for country/folk and we chase that up a bit more. George gets TWO songs (count them, TWO) on the album. Solos are on the wane however.

Help !

This largely acoustic-guitar based uptempo number is enhanced by George’s signature riffs.

This has a rather odd octave-based riff solo section, which sounds a bit half-hearted.

The tone pedal returns here which explains the lack of attack on every riff phrase. I rather like the mid-section in this George tune, which again sounds quite natural and seems to have a bit more life than the verses. I can see this song having more of a country rhythm which might have tightened things up a bit, and the tone pedal at the end is a bit messy. But its a great bluesy melody.

A brief respite from the tone pedal and George gets his Chet Atkins back on. I like the vibrato George tries out, particularly on the ending riff.

You’re Going To Lose That Girl

One of my favourite songs for the backing vocals. If it weren’t for George’s solo, more Byrd-comparisons would be made.

This sounds as if they double-tracked George’s guitar, it does seem to have an unusual presence.

Possibly the first George earworm. I know I haven’t been able to get the damn thing out of my head for a week or more! Again, George goes for that strong harmonised bluesy melody and its a great mid-section. He does a simple call-and-answer solo with the piano, which doubles with the verse riffs. You can see how much better a country rhythm works here, as George is beginning to oscillate with what he loves (RnB) and what he knows (rockabilly), but the big change is yet to come.

SINGLE: We Can Work It Out /Day Tripper

Another single of portents. That’s George’s sturdy tambourine work on the A-side, but it’s the B-side that’s the surprise, the first serious RnB-riffer. George and Paul share the main riff, and while John plays the solo, that’s George playing those ascending notes which sound like he’s fiddling with the tone pedal a little more successfully this time.

The following people thank ewe2 for this post:

Beatlebug, MarthaI'm like Necko only I'm a bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin and also everyone. Or is everyone me? Now I'm a confused bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin everyone who is definitely not @Joe. This has been true for 2016 & 2017

10.33am

8 January 2015

Offline

OfflineRubber Soul

Everything changes on this album. George and John get Strats, George names his Rocky and it gets a lot of work over the coming years. And something even more momentous: George begins playing the sitar and tamboura. Of all the Beatles, it was always going to be George who could pick up a completely different musical system and instruments. That he could blend them successfully with Western popular music and by transmission, popular culture is one of his greatest gifts to all of us. It also had other effects: it enabled the Beatles to write different songs, and it sharpened George’s ability on his original instrument by a long way. It’s from here that his accuracy with bends and slurs becomes much greater.

I won’t go on about the beginning of this song, it’s just great. I’ve worked out how to play the bass to it and keep time and I’m satisfied with that 😀 It’s very interesting that he took a Duck Dunn (legendary RnB bassist) lick for the song, which just goes to prove the songs credentials, the fluid solo is one of my favourites too.

Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)

The first appearance of sitar. We know from bootlegs there was an alternative call-and-answer lick originally in the B-sections, but note how the flat structure of the song works wonderfully with the sitar and it wasn’t really necessary to fill that space.

Nowhere Man

This has Rocky’s first solo, double-tracked to sound almost Rickenbacker-like but far more trebly with that sweet harmonic at the end like a sunburst.

Byrds comparisons aside, listen to the assurance in George’s voice, his melody jumping between 3rds and 7ths at the end of the phrases, and again the flatness of the structure with no middle-eight or solo. The lyrics are also a statement of intent: it’s George telling us he’s on his spiritual path and there’s always time for you to change, too. Note how the gorgeous harmonies burst out on the telling phrases.

Dig those Strat stabs!

Did I mention already that I like this song? It just seems to have a great feel and life to it compared to many of their country-flavoured numbers and I think George uses Rocky on it, the solo is very plunky in the trebly way and it’s quite extended, allowing George to string some nice licks together.

That signature riff is George again.

It sounds like the tone pedal at work again in the coda here.

A SECOND George song (count them, TWO). George specifically credited the Byrds for inspiring this. It shares some obvious similarities with Think For Yourself , there’s the fantastic harmonies, he’s got the 12-string happening I think and it’s definitely a drone-based song. It’s a gorgeous, dreamy thing.

George breaks out the Strat for some bendy country licks on this blighted song.

SINGLE: Paperback Writer /Rain

More signature riffing on the A-side and on the other A-side George and John join forces for a cascade of arpeggiated gold. Apparently George used a Gibson SG on both tracks and on a few songs on the following albums.

Revolver

We come now to a crucial crossroads for George. It’s somewhat ironic that George has an exclusively-Indian based song in his THREE (count them, THREE) songs before he went to India in about August of 1966, and here he gets the first song of the album also. The Indian influence also begins to affect his other songs in subtle ways, the most important of which for me is that he started using dissonance and strong chromatic contrasts. There are a few mysteries about who did what when on this album which are complicated by misleading notes and memories. It’s one of the frustrations of being a Beatles fan, wanting to know the last detail that’s forever out of reach.

Again a strong bluesy melody, and a now-characteristic sarcasm. Am I just imagining that even Paul’s lead sounds a little raga-like? It features another initially confusing beginning a little differently than Drive My Car , but the similarity is probably deliberate. It’s another simple rhythm like his Rubber Soul songs but its more driving and stripped-back. Mostly based on alternating 7ths and 9ths, it’s a kind of RnB drone with just two chords for the chorus. Instead of a clear contrasting middle eight, George goes for a sort of tacet, changing the rhythm of the vocal melody over the same backing and just pausing on a C 7ths, then it’s back to the verse-pattern for Paul’s solo. It’s a perfect pop vehicle, nothing wasted, and the idea of repeating the solo on a fade is the finishing touch.

The story goes that once they heard backwards guitar they had to do it, and George is said to have worked out a solo backwards and played it so when it was reversed it would come out forwards but sounding backwards way for this song. It’s hard to do this even for simple phrases, even for trained musicians, and George did something more complicated! That gives you some idea of his musical tenacity and work ethic to make this song shine.

The second song, and the obviously raga-influenced Indian style was probably played by his Indian friends. The lyrics paint a much darker, and honest, picture of Beatlemania than anyone would admit to for decades and its funny how everyone seems to have ignored it to talk about the Indian music instead.

This was a very last-minute addition to the album, and once again George demonstrates how much he could add to a song, playing bass and lead and backing vocals. By now John and George were very good at their guitar interplay which recalls Rain slightly, and notice how high George can harmonise! One of my favourite George basslines, and not the last! The Gibson is scalding hot on this one.

George and Paul this time, we think..maybe. It’s a pity we can’t trust even the notes that were left if Ken Scott’s story about George’s demo in ’68 is any guide. Still, a great part, and again the Gibson cuts through.

George pulls out the heavy 7th riffs again for this one, which I’ve noted does seem to have an uncomfortable RnB/country feel to it, which they had done more successfully on other songs.

The third (count them, THREE) song and the oddest. It’s been said to me that it feels like an older throwaway jazzed up but I’m not so sure. This is where Georges work with dissonance first appears: the heavily-chromatic piano motif lets the notes ring and you hear the dissonant harmonics rise from it. He adds to this by a rhythm that suggests an odd time signature, yet the sheet music proves that it’s all straightforward 4/4, just with a melody that deliberately pauses off the beat. The C-section, less a break than a complete phrase with lyrics and no solo, seems to amp up the melodrama and does strongly suggest a confused mind, something Lennon would use later in his lyrics. On top of this, the backing vocals are also deliberately dissonant, resolving the harmony as a major scale but not a blues scale: the why in the don’t know why, should harmonically resolve as a flattened 7th but they resolve it a full tone above, which makes it sound “wrong”, and play this up in the coda with Paul sounding oddly Arabic.

George was putting his guitar through a Leslie organ speaker a lot on this album, and it’s very strong here in the solo. And note the sequencing of the album, here is a Paul RnB song with a very similar rhythm that does resolve harmonically by comparison to George’s previous song, like a conventional version of it!

Literally starting with George on tamboura drone and featuring him on guitar and sitar also, this was the track that got them putting everything through a Leslie speaker once they’d tried it on John’s vocals.

SINGLE: Strawberry Fields Forever /Penny Lane

George’s guitar is prominent throughout the A-side: the sweet backing of the first part, it’s him on svarmandal in between the remaining verses and it’s his amazing psychedelic guitar phrases thereafter. George is basically invisible on Penny Lane , only audible as backing vocals, and I can’t hear any of his guitar.

The following people thank ewe2 for this post:

Beatlebug, MarthaI'm like Necko only I'm a bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin and also everyone. Or is everyone me? Now I'm a confused bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin everyone who is definitely not @Joe. This has been true for 2016 & 2017

10.33am

8 January 2015

Offline

OfflineSgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

George has said that he was basically disconnected from the process of this recording, having returned from a life-changing trip to India, and wasn’t that interested in the minutiae of the songs. Except for his song, he only pops up occasionally on guitar and is most audible as backup vocals, but was more involved in the process than he remembered, going by Lewisohn’s records.

Sgt. Pepper ‘s Lonely Hearts Club Band

Unusually, George plays the main rhythm guitar (believed to be Rocky) on this song, with Paul on characteristic lead.

With A Little Help From My Friends

George plays a very short lead here, the sound is shiny and polished, of sliding intervals down to a sparkling finish.

The tamboura features here particularly strongly on the mono mix, and George did quite a bit on here. I don’t know which parts John and George played on electric guitar, but George also added acoustic which is just audible in the second verses onwards, it’s a little clearer on the Yellow Submarine Songtrack mix.

George gets a very sweet sound from Rocky on this track laying down the stabs, and added tamboura in the break.

George has a little more space to to really twang on this solo, which is the only substantial one on the album.

Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite!

George plays harmonica!

Within You, Without You

George’s main contribution to the album. He plays several instruments, but the stand-out one is the sitar, which leads this singular fusion of Indian and Western music, following the melody of the verses and and a wonderful call-and-answer with the string section. It is a very complex song rhythmically and melodically and I prefer to leave Alan Pollack to explain some of it. It’s evidently not traditional in either musical culture anyway, it’s George’s own version!

The lyrics are still some of the most profound I have ever heard, especially from a Beatle; only John comes close to this kind of spirituality with Across The Universe but is poetic rather than as concrete as this. Like A Day In The Life , this is the serious side of the album, echoing a spiritual Revolution which often motivated the 60’s counter-culture to action, however brief and futile, as that generation again descended into selfish greed and dragged the rest of us down with them. These were the highest ideals they ever aspired to, but it was quickly dismissed as fashion. I agree with Pollack, that the laughter following it wakes us from a dream, but is also derisive.

That’s George on Rocky with the opening flourish, but most of his contribution is backing vocals.

Sgt. Pepper ‘s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise)

It’s mostly George’s guitar on this one.

Maracas, and possibly inputs of ideas but that’s it for this album.

Magical Mystery Tour

This album is a bit of a mess and George doesn’t do a lot on most of it except on his THREE songs (count them, THREE).

George goes even further into dissonance and drone composition and the lyrics match the obsessive recurring quality of the music. I find the backing vocals to be the spookiest bit really, and for some reason I’ve always associated the lead vocal with the dead captain of Darkstar, its the sort of thing I can imagine him repeating in his block of ice, floating out in nowhere.

Rocky’s contribution isn’t all that important to the song but does get played in the promo clip, so there’s that.

George’s much-maligned solo (even the Rutles parody is longer) isn’t a pointless exercise at all. It’s there as a break from a repetitive structure and is answered by the orchestra. I won’t repeat the absolute tosh Ian MacDonald rants about this track except to note that he characterises the Olympic engineers as being “shocked” at the “careless” mixdown process, despite George Martin overseeing it. And George played violin on it but I’ve never heard it myself.

The solo was George, get over it 😀 John might have been able to play the beginning of it, but not the complex 3rd intervals which require some dexterity.

It would have been interesting to have this on Peppers, a logical extension of George’s interest in dissonance, playing with time signatures and unusual chord intervals. And the lyrics are certainly a sardonic antidote to Within You Without You . In the verses, the discomfort of the hanging Bm7/A is resolved by the E7 only to undercut by the D while a joyful pandemonium of noise continues underneath and sometimes well on top. The whole song is an example of George’s sense of humour, which has been completely miscast with some fury by various commentators because it refuses to take itself seriously. Too bad, so sad. I like it.

I find it more difficult to like the treatment of this George song, the melody and basic idea is fine, but it does go very over the top psychedelic-style. Again, they’re not taking themselves seriously and George gets in a dig or two at his generation edgeways, so it’s all good. Too much, man!

The Beatles

When you have the diametrically-opposing views of Ken Scott and Geoff Emerick, you’re reminded just how everyone takes sides on the Beatles and how that affects their recall. In other words, it’s not a big Paul album, but its certainly a John album with a fair whack of George. Like the others, George reassessed his instrumental preferences here, and he steps up a notch in melodic approach and makes some important contributions on bass too. I assume he used Rocky a fair bit and we know he probably used a Fender Jazz bass, whereas John preferred the VI. But the most important guitar is Lucy, the cherry-red 1957 Les Paul Eric Clapton gave him. It’s on a few tracks here, most importantly it’s what Clapton used on George’s most important song to date. The demo for it and a number of others was put down during the sessions so George could get the others to think of parts for them, which mostly happened. With Lucy, George developed a vicious tremolo style that he often employed and it’s an embryonic form of his slide technique later if you think about it.

We know that according to Ken Scott, George AND John contributed to the drumming here.

Once again George and John combine to make an almost orchestral wall of guitars, with George taking the high note towards the end of the last extended-length chorus.

Just a few licks here and there, nothing much.

George gave the others notice that he wasn’t kidding around any more, it’s a good song and if it took bringing in someone else to play the solo, then maybe it would get the attention it deserved. As a result, everyone behaved and worked for the song, and the result is a classic. Many of us fans love the acoustic demo on Anthology just as much as the final result.

Lead on this one, but it’s really just following the riffs and doing background stabs.

It’s not George on the main solo, but he does his usual thing of tasteful little licks around the chord changes.

This acerbic little number features George on bass as well as the tart vocals. It’s hard not to join in with gusto on the final verse! Again he undercuts a song with his …one more time second coda complete with piggy grunts.

Lucy’s characteristic wail leads all the riffs, dig that tremolo!

First John and then George take turns on the solo, both of which sound like they’ve been varispeeded and certainly flanged, particularly George’s which sounds a bit mental!

Everybody’s Got Something To Hide Except Me And My Monkey

Lucy’s distinctive corrosive tone again on this rocker, those tremolos were so effective.

George got to do both tasteful little arpeggios and the broad-stroke solo, notice how simple his solos are now. This would feed into the next period.

Clearly Lucy again, particularly on the shredding solo, but also in the wall of noise and the chorus riffs.

Another directly spiritual song, this beautiful quiet tune is a welcome contrast in the sequencing, and it’s so simple it doesn’t even need a solo but has a fascinating end, complete with moans and rattles and another undercutting moment, a simple tom-shot.

Here George uses Lucy to great effect, it’s got his classic late-Beatles style on it, influenced by Clapton to my ears.

No, that’s not George on the lovely solo it’s John! George is playing the bass instead! Wooo!

This is finally where George gels his RnB sound. You can hear the descendants of this style in This Song and even Crackerbox Palace. There is a mystery about who played the drums on it; one assumes it was Ringo but Ken Scott says it was recorded at Trident before Ringo came back so it must have been Paul. But it doesn’t sound like Paul to me. In any case the stinging solo is George on Lucy.

SINGLE: Get Back /Don’t Let Me Down

I’m fairly sure George plays the rosewood Telecaster on this single as it comes from the same sessions as Let It Be , but he was also using Lucy at times too. George holds down the rhythm duties on the A-side, while on the B-side he plays those delicious sliding intervals down to the major 6th in the verses and plays the riff in tandem with John on the break.

The following people thank ewe2 for this post:

Beatlebug, MarthaI'm like Necko only I'm a bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin and also everyone. Or is everyone me? Now I'm a confused bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin everyone who is definitely not @Joe. This has been true for 2016 & 2017

10.34am

8 January 2015

Offline

OfflineLet It Be

This time George quit on the album, tired of the Partnership badgering him or ignoring him and only came back with Billy Preston and a demand to move out of Twickenham to make them get something constructive done and behave in front of the cameras. Meanwhile, his stack of songs began to pile up and he began to deliberately try some out on the others to see if he’d get any bites, and stockpile them for a time when he could do a solo record. I’m not sure whether that was a sign that he thought the band was doomed or was hoping they could get another break from each other and he could do his solo record then, but he was clearly planning for one. He used his new rosewood Telecaster a lot on the tracks, including the rooftop concert, but it sadly never got a name. I wonder if Dhani has named it, he loves it! What is apparent, though, is that the promise of the more laid-back style of slurring and simple chords bore fruit, showing a more relaxed approach, and the relaxation is what gives his riffs and solos a more stable, mature quality.

George playing “bass” on an acoustic.

The first of the rooftop concert songs, and George is doing his two-note slides everywhere, and gets to launch into a solo that frankly talks. It sounds like George has the love of playing guitar again, but its not stuttery squiggles, it has a real voice.

This song is still contemporary 50 years later. George writes the rhythm as a waltz verse and a rocker chorus, and it’s a simple AB-break pattern. George alternates between almost weary verses and intense almost-yelling choruses and his sharp-tongued Lucy goes wild with frustration. The song doesn’t end so much as peter out in exhaustion. It’s a powerful performance, and Paul, digging deep and contributing some great keyboard work, does well to keep up with it!

The curious thing about this song is the dithering over which George solo to use. My already-stated preference for the single version over the album and LIB versions is based on the general fluency rhythm and melody of its Leslie-splashed style, clearly the style George was building towards. By contrast the album version looks backwards as a Lucy wail that almost but doesn’t quite come off. The LIB version is a non-Leslie compromise between the two that doesn’t have the angst of the album version but doesn’t swing like the single. All three solos affect the song in different ways, whether you like its general production or not, and it’s a surprising situation for such a strong song to be in.

One of the great frustrations of the movie is not being able to see George play much on this one, but that’s him on the Tele doing the heavy lead behind Paul’s vocals. Is there anything greater than that intense tremolo in the break before the verse returns after the middle-section? It’s as if the guitar, hyped up from the vocals, is stumbling back from the force of it. You can also see George alternating between a pick and his fingers, which is very interesting but alas too brief to get a real handle on.

Simple rocker with a solo that George absolutely nails on his Tele. He travelled so far in a few short years and it has fluency and space and it’s a really happy moment in the song for everyone.

George contributed tamboura and Wah-Wah pedal guitar to this, and the tamboura is particularly effective.

John actually plays some lead on this simple 12-bar blues of George’s, who just plays acoustic and sings. Unlike real blues, it’s a happy song about love found, not lost.

Abbey Road

At last, like a phoenix from the ashes, George sprang from the Beatle’s dying embers with a song that finally made it as a Beatles A-side single and the second-most covered Beatles song, and another which became an FM radio standard for the next 50 years and counting. That’s not bad for someone whose arguably best work was yet to come and whose recognisable style was finally to come to rest as a shimmering slide feel, born of the work done back on the White Album with Lucy and years of honing his bends and tremolo technique. It sounds so effortless and simple but it takes real finger strength to make those bends work and real depth of feeling and connection to himself to reach that expressiveness.

The first surprise is George using the tone pedal with a slide and shimmers on the verses. The second surprise is that bendy solo, parts of which are very similar to licks in Something .

The second-most covered Beatles song is a mixture of chromatic harmony and descending scales. It’s interesting that this is the second song of that kind after While My Guitar Gently Weeps , but instead of using minors, he’s accenting the 7ths. The B-section takes on the modulation suggested by the signature riff, which is always a risk and not something easily resolved without some kind of obvious construction but George treats it as a natural crescendo leading into the sublime C-section verse pattern and one of the greatest solos of all time. That it actually sounds natural is amazing, but he tops it at the end of the song by using the modulation as a false ending/resolution, almost like a chromatic passing harmony and then uses the same initial riff to resolve it. And most people don’t notice this magic trick because they’re humming the melody!

There are lots of things I love about the solo, which is rightly said to hint at George’s later slide style. It really is talking, the kind of solo that says what the singer can’t express, sliding, bending, climbing and descending into a kind of wordlessness itself before effortlessly recalling the signature riff into the final A-section. You can listen to it a thousand times and still be entranced. A solo to taunt would-be guitar heroes for the ages, but I challenge anyone to find a more singable solo (ok maybe it’s just me who sings it, badly in showers).

We haven’t even got to the lyrics, pondering the mystery of attraction (thanks to a James Taylor line) and the conviction of love. No wonder Frank Sinatra liked it.

George takes on both guitar and bass chores on this jaunty two-step vamp, virtually the last of its kind. I’ve avoided reviewing this song up to now but it does need noting. I don’t hate the song myself, but it does evoke strong reactions, and I think unfairly. It’s not as repetitive as Your Mother Should Know with the corny backup singing, for instance. It has the unusual onomatopoeic gambit of the actual hammer sound, and a most unusual lyrical subject. My impression is that Paul might have been influenced by his brother Mike’s success in The Scaffold with hits like Lily The Pink, a sense of humour that definitely runs in the McCartney clan. Be that as it may, it shows George’s dedication to supporting Paul on this album, which is pretty impressive given the differences they were having by now, and he even gives Paul a go on the Moog (at which he is no slouch either) while he plays very-close-to-slide guitar in the background and that doubled solo. I particularly like how he uses the bass to almost comment on the riffing above it. If we want to give Octopus’s Garden some credit, which we should, then at least credit the musicianship on this song too even if you despise it.

A slow simple rocker, and George’s guitar is almost dotty in the way it repeats the riffs in the middle-eight, like a confused duck quacking around; I don’t know why but it makes me laugh for some reason, perhaps its the contrast with Paul’s roaring vocal. That and the searing trebly notes at the end are my favourite bits of this song, as is the slightly deranged backup singing. Actually I think I find this song funnier than the previous song, for all the wrong reasons, it must be age.

Often overlooked because it’s “just” a Ringo song, but it features a really strong performance from George, from the fluid and sparkling intro and the joyful solo to the snappy ending and all the licks in between. It virtually carries the song.

I Want You (She’s So Heavy)

George slips back into tandem mode with John on this heavily-jammed song, apparently using Rocky because he’s using its pickup switch audibly. He supports John’s great guitar part without getting in the way and of course there’s the massive guitars at the end, achieved with god knows how many overdubs, its a wall of sound. You can hear George start the song with some lead over the signature riff, and then switch immediately into rhythm guitar mode with licks and chord stabs which are like finishing the sentences of John’s guitar melody.

The other massive George song on the album, but he uses acoustic guitar backed by a string section, and the Moog instead of an electric. The acoustic gives his chords and riffs a warmth (see what I did there), and the song itself lulls you by its verses and then zaps you with that middle-eight out of nowhere. The Moog is used with great effect, using different patches on each octave of the middle-eight to give a different timbre, like a little showcase for electronic instruments, and then almost like an organ with a flute-like tone, playing long melodic phrases in the verses. Overall the song oozes good feeling, like a hot cuppa on a cold spring morning. By now George’s songwriting talent has matured so much that everything hangs together so well melodically; even the surprise of the middle-eight feels agreeable, an effect much less obvious than older songs. Whenever I feel down, this song is always a comfort, always telling me it’s alright, the sun will return, like winter to spring.

George contributes his gorgeous harmonies and brings the Moog out for a solo.

George had a lot more to do on the Huge Melody than John: not only did he play lead guitar throughout, he also played bass on Golden Slumbers and Carry That Weight , which is all I’ll say about those songs. George sounds like he’s using Rocky on this song, it’s got a twangy quality in the upper range that Lucy doesn’t have, and he Leslied the output all the way through.

George continues leading the band with some nice two-note slides and more Leslie-splashed 6ths.

Just the chord progression on this.

George does his reverby call-and-answer style, harking back to the old days with a little more polish and less stutter. It sounds so tantalisingly close to slide with that distorted two-note slur.

She Came In Through The Bathroom Window

The call-and-answer style of riff again, but it has never been as successful as this. It sounds bird-like to me, a magpie sitting by the window singing and watching the goings-on with Paul and his missus. The verse riffs are sunny and shimmering, the choruses a little more sardonic and knowing.

It’s important as the last hurrah and a nice round of solos from everyone, especially Lucy.

Assorted Things

A couple of things left out that didn’t fit. I’m avoiding using the excuse of demos to pull out the songs he would later do for All Things Must Pass , it’s truly a different George era.

A B-side, which we are lucky to get; it should have been on an album. I do like the demo version on Anthology 3 , as much as the finished version. It’s a cracker of a song, which I’ve previously noted is fantastically driven by Ringo’s drumming, as well as the tandem riffing with Paul. He sets up the song with simple slide riffs as both instrumental break and introduction into the verse. The verse has an chord progression that almost traces a complete diminished triad and ends up at an odd A minor which gets its resolution ignored for the 2nd verse until relief comes on the middle-eight. That throws in an rising chromatic progression, heavy on the augmented chord to resolve back into the chorus over which George wails on Lucy and then back to the verse. Lyrically, George throws in his love of opposites, a ‘love that’s right is only half of what’s wrong’ and a ‘short-haired girl that sometimes wears it twice as long’.

It may seem unfair to pull this bootleg out, but it’s a good George song even if it went unreleased in its original form. George didn’t do that many two-step vamps but this was the psychedelic era and why not try his hand at one. I feel he was pushing the limits of what could be done with the format with it, and although the guitars are terrific and the lyrics enjoyably biting, he didn’t condense it enough perhaps or find a striking-enough middle-eight or maybe just that 6/8 bit annoyed everyone too much. As it is, the recording is left too rough, needing an edit or two and an earlier fadeout at least (NOT what Emerick did to it however!). It’s a genuine what-if relic.

Conclusion

It’s one of the ironies of the Beatles that George would start peaking so close to the end of the band. His wonderful slide style would never be heard on a Beatles record, my favourite being the How Do You Sleep? solo. In the last couple of years of the band’s existence, he reconnected with his guitar development and incorporated a more relaxed, slurring, interval-based style which would make that possible. The influence of Clapton and the general British RnB/blues scene should be acknowledged; George’s post-1967 playing has a lot in common with late Yardbirds and Cream for instance. I also think a better sense of himself, being able to articulate who he was, and that combined spiritual and personal development went a long way in relaxing his playing and explains why his contributions to the last two albums are more organic and effective. It’s a long way indeed from the stylistic rockabilly squiggles, chiming 12-string chords, and corrosive needle-sharp solos, yet somehow George’s final phase after the Beatles showed qualities of all where appropriate. He was a very complete songwriter and instrumentalist in the end, and maybe the one member who truly outgrew the Beatles. He changed his style more than the others, he was at least as adaptable as Paul if not more, had a greater instrumental range than John, and wrote more songs than Ringo 😀

Now we’re at the end of this series of musings on the different aspects of each member of the Beatles playing and songwriting styles and George’s took longest to write, but I think John’s was still the hardest. But when I researched again to write them, the conclusions I drew surprises me.

I discovered John to be a more adaptable instrumentalist than first sight but also the most resourceful songwriter. But it remains true that he wasn’t interested in the details or exploring ideas more completely across several works once he’d satisfied himself, in contrast to Paul and George.

I learnt what I had suspected about Paul all along: he was a major talent would have arisen given any encouragement, but if I look twice, I also see someone who gets applauded for the things he didn’t have to work at, and the things that he did work at, his bassplaying particularly, are just accepted as part of the package. He’s like that older style of songwriter who just happened to be in a big band and likes performing as well.

I am still astonished at the depth and detail of Ringo’s work and the great gift of his faultless timing. It says a lot about the talent of the band that Ringo would himself grow into songwriting but remains mainly a great, great drummer.

And George, who had to change his approach several times, took that adaptability and ran with it, growing up as a person and songwriter in public, has perhaps my greatest admiration for getting through it and winning his own place as one of the greats.

The following people thank ewe2 for this post:

Beatlebug, Bongo, MarthaI'm like Necko only I'm a bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin and also everyone. Or is everyone me? Now I'm a confused bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin everyone who is definitely not @Joe. This has been true for 2016 & 2017

11.41am

Moderators

15 February 2015

Offline

Offline@ewe2 Terrific, as usual. You shined especially on the Abbey Road section and the conclusion– your dissertation on ‘Something ‘ nearly made me tear up, it was that brilliant.

However, being a dyed-in-the-cloth editor, I noticed a few small details which you might wish to correct (under spoiler):

1. According to Joe’s page (and other sources), George Martin’s part in Baby It’s You was on a celesta, not a glockenspiel. (Apparently they sound quite similar.)

2. It’s Crackerbox Palace, not Crackerjack Palace.

3. There was something else, but I forgot what it was.

ewe2 said

<big slice>

<trim>

There are lots of things I love about the solo, which is rightly said to hint at George’s later slide style. It really is talking, the kind of solo that says what the singer can’t express, sliding, bending, climbing and descending into a kind of wordlessness itself before effortlessly recalling the signature riff into the final A-section. You can listen to it a thousand times and still be entranced. A solo to taunt would-be guitar heroes for the ages, but I challenge anyone to find a more singable solo (ok maybe it’s just me who sings it, badly in showers).

<big slice>

YESSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS

It took me the longest time to sing this one (and I sing every Beatles solo I can get my ears on) because the keys go all over the place, and I’d always turn up at the last verse in F, or something. Ergh. But when I learnt the chords to the song, they kept me in key and it’s my favourite part of the song to sing. Well, the ‘I don’t know’s are pretty fun too. Okay, the whole thing is… yeah, it’s just brilliant. 🙂

Did I mention George is my favourite (by a very small amount over Paul)?

The following people thank Beatlebug for this post:

ewe2([{BRACKETS!}])

New to Forumpool? You can introduce yourself here.

If you love The Beatles Bible, and you have adblock, don't forget to white-list this site!

12.50pm

8 January 2015

Offline

OfflineThanks for the errata, @Beatlebug, much appreciated. If you find something or remember it, be sure to mention it. Crackerjack is the name of an Australian movie and I was listening to podcasts while I was writing and probably got my wires crossed there! I do enjoy George especially on the White Album and Abbey Road just in terms of his sheer technique and feel. I find his solos and even licks are singable, you can’t say that about many guitarists.

The following people thank ewe2 for this post:

BeatlebugI'm like Necko only I'm a bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin and also everyone. Or is everyone me? Now I'm a confused bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin everyone who is definitely not @Joe. This has been true for 2016 & 2017

1.44am

15 May 2014

Offline

OfflineYou’re The Man, @ewe2. Thanks again for all the insight and the effort.

The following people thank Oudis for this post:

ewe2“Forsan et haec olim meminisse juvabit” (“Perhaps one day it will be a pleasure to look back on even this”; Virgil, The Aeneid, Book 1, line 203, where Aeneas says this to his men after the shipwreck that put them on the shores of Africa)

3.21am

Reviewers

29 August 2013

Offline

OfflineOudis said

You’re The Man, @ewe2. Thanks again for all the insight and the effort.

Yes indeed. The whole series of posts has been just amazing, with some great insights.

@Joe I’m not sure if these could be articles somewhere on the site?; I know they are opinion but (IMHO) they’re too good to be (relatively) hidden away in the forums.

The following people thank trcanberra for this post:

ewe2, Oudis==> trcanberra and hongkonglady - Together even when not (married for those not in the know!) <==

9.26am

8 January 2015

Offline

OfflineAs flattering as the suggestion is, I’d like more people to see them all and pipe up with errata so that in the case @Joe thinks it’s worth enshrining, I’ve ironed out the kinks. I’ve already re-edited each a few times and probably will need to do so again.

The following people thank ewe2 for this post:

trcanberraI'm like Necko only I'm a bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin and also everyone. Or is everyone me? Now I'm a confused bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin everyone who is definitely not @Joe. This has been true for 2016 & 2017

While I applaud everything @ewe2 has written, and it does deserve more exposure, I don’t think I’d want to move it into the main part of the site for a few reasons. First and foremost, it’s my domain and I’m fairly territorial!

Secondly, I try to make the song and album articles fairly neutral, whereas these are one person’s opinions. But there’s no reason why these couldn’t be added as comments below my features, as many hundreds of others have done.

Thirdly, it’s ewe2’s content! I’m very pleased that it was published here first, but people have started websites on far less. This could be the basis of a really interesting musicology blog. That’s not up to me though.

I think there is a space for a more musicological approach which I’m not really able to fill on my own. Although they’re also fairly opinionated in places, I have considered republishing Alan W Pollack’s acclaimed articles on each of the songs (they’re under CC licences) as appendices to my articles. I’ve not really worked out how I might be able to incorporate them with the right credit and separation (I’d need to credit Pollack for his words but I wouldn’t want people to think he wrote the whole site, or that everything was under a CC licence). I should probably put some proper thought into it.

@trcanberra

The following people thank Joe for this post:

trcanberra, ewe2Can buy me love! Please consider supporting the Beatles Bible on Amazon

Or buy my paperback/ebook! Riding So High – The Beatles and Drugs

Don't miss The Bowie Bible – now live!

12.51am

8 January 2015

Offline

OfflineYeah they’re written from a not-so-musicological fan’s perspective, but they never would have been written at all except for @Joe and his site, I’m not trying to steal any thunder here. I’d like to see more Pollack here just to see the reactions, given he’s already run them through some harsh internet musicologists. The value of Pollack to me is that you do run out of theory as a response, you always have to fall back on your feelings and opinions. It does make it tricky to add him to the existing structure so that commentary can be added. My articles are a suggestion to try and look at the band from a specific thing they were good at and write something around that, and I think that’s far from a done idea, yet. But I need a rest from it for a while.

The following people thank ewe2 for this post:

Oudis, JoeI'm like Necko only I'm a bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin and also everyone. Or is everyone me? Now I'm a confused bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin everyone who is definitely not @Joe. This has been true for 2016 & 2017

7.49pm

9 March 2017

Offline

OfflineI stumbled up on this list while looking for things to do and i must say, good job @ewe2 good job. One thing i found interesting is that Ken Scott claims that Savoy Truffle was recorded before Ringo came back, odd considering that the song was recorded in October which is a month after Ringo returned and i’m 1,000,000% sure that it’s Ringo on drums here.

The following people thank Dark Overlord for this post:

ewe2If you're reading this, you are looking for something to do.

12.52am

8 January 2015

Offline

OfflineDark Overlord said

I stumbled up on this list while looking for things to do and i must say, good job @ewe2 good job. One thing i found interesting is that Ken Scott claims that Savoy Truffle was recorded before Ringo came back, odd considering that the song was recorded in October which is a month after Ringo returned and i’m 1,000,000% sure that it’s Ringo on drums here.

Thanks, I should revisit and edit at some point, as I mull things over. Savoy Truffle ‘s story is a bit odd, we no longer have George’s memories of course; but I just cannot hear Paul doing that intro fill or any of the fills for that matter. If we saw the layout of the basic tracks it would give us a clue, maybe someone did some basic time on a track and that got bounced out once there was enough backing and Ringo came back and did the drums later (which is not so unusual, he did it for Paul’s track Why Don’t We Do It In The Road?). Compounding the problem, most stuff that I’m aware they did at Trident was almost never properly documented.

I'm like Necko only I'm a bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin and also everyone. Or is everyone me? Now I'm a confused bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin everyone who is definitely not @Joe. This has been true for 2016 & 2017

2.34am

9 March 2017

Offline

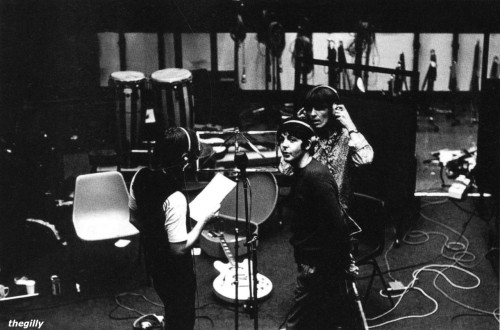

OfflineTo be honest, i think Ringo played drums on the original track along with Paul’s bass and George’s rhythm guitar. Interesting that you say that there’s no documentation for the Trident sessions though because although there’s no proper documentation, The Beatles actually took photos of every song off The Beatles AKA White Album that was recorded there:

WARNING:

BIG PHOTOS AHEAD!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

These photos and in the case of Hey Jude video footage, we have proof that George used his Gibson Les Paul on Martha My Dear and Savoy Truffle , his SG on Dear Prudence , and that John used his Gibson J-160E on Hey Jude . Hope i didn’t get too off topic.

If you're reading this, you are looking for something to do.

1.14pm

8 January 2015

Offline

OfflineThat is something I didn’t examine in more detail: the guitar phases George went through, it’s been done better by others. Lately I have been wondering about George’s SG (I believe it’s the one he gave to Clapton who had the Fool repaint it and played in Cream), he doesn’t seem to have kept it for long.

The following people thank ewe2 for this post:

BeatlebugI'm like Necko only I'm a bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin and also everyone. Or is everyone me? Now I'm a confused bassist ukulele guitar synthesizer kazoo penguin everyone who is definitely not @Joe. This has been true for 2016 & 2017

1 Guest(s)

Log In

Log In Register

Register

![[?IMG]](http://i.imgur.com/lPJr2G4.jpg)

![[?IMG]](http://i.imgur.com/KkKuXyB.jpg)

![[?IMG]](http://i.imgur.com/mVkaIGZ.png)