Cover artwork

Although the music of Sgt Pepper was a major step forward for popular music, the cover concept was also a considerable innovation. It nearly didn’t happen, however. The Beatles had to be talked out of using an illustration by The Fool, the design group that painted the mural on the side of the Apple shop in London.

The whole mood of that was quite interesting, because the original part of the commission was based on the fact that Robert [Fraser, art director] absolutely hated the original of the cover by this group called The Fool. He thought it looked like psychedelic Disneyland, which it did. It was a mountain with all these little creatures on it, slightly cartoony. Robert said to The Beatles, ‘You just cannot have this cover, it’s not good enough. You should get Peter and Jann to do it.’

Groovy Bob, Harriet Vyner

Peter Blake and Jann Haworth were married at the time, and had exhibited separately at the Robert Fraser Gallery in Duke Street, Mayfair. Fraser was a key figure in Swinging London’s art scene, and had an unerring knack for spotting important artistic talent at an early stage.

Once The Fool’s original cover concept had been discarded, McCartney, Fraser and the artists worked on another concept which began by marrying The Beatles’ northern roots with the world of celebrity in which they now resided.

I had the name so then it was, ‘Let’s find roles for these people. Let’s even get costumes for them for the album cover. Let them all choose what they want.’ We didn’t go as far as getting names for ourselves, but I wanted a background for the group, so I asked everyone in the group to write down whoever their idols were, whoever you loved. And it got quite funny, footballers: Dixie Dean, who’s an old Everton footballer, Billy Liddle’s a Liverpool player. The kind of people we’d heard our parents talk about, we didn’t really know about people like Dixie Dean. There’s a few like that, and then folk heroes like Albert Einstein and Aldous Huxley, all the influences from Indica like William Burroughs, and of course John, the rebel, put in Hitler and Jesus, which EMI wouldn’t allow, but that was John. I think John often did that just for effect really. I first of all envisioned a photograph the group just sitting with a line of portraits of Marlon Brando, James Dean, Einstein and everyone around them in a sitting room, and we’d just sit there as a portrait.We were starting to amass a list of who everybody’s favourites were, and I started to get this idea that Beatles were in a park up north somewhere and it was very municipal, it was very council. I like that northern thing very much, which is what we were, where we were from. I had the idea to be in a park and in front of us to have a huge floral clock, which is a big feature of all those parks: Harrogate, everywhere, every park you went into then had a floral clock. We were sitting around talking about it, ‘Why do they do a clock made out of flowers?’ Very conceptual, it never moves, it just grows and time is therefore nonexistent, but the clock is growing and it was like, ‘Wooah! The frozen floral clock.’

So the second phase of the idea was to have these guys in their new identity, in their costumes, being presented with the Freedom of the City or a cup, by the Lord Mayor in all his regalia, and I thought of it as a town up north, standing on a little rostrum with a few dignitaries and the band, above a floral clock. We always liked to take those ordinary facts of northern working-class life, like the clock, and mystify them and glamorise them and make them into something more magical, more universal. Probably because of the pot. So we would be in presentation mode, very Victorian, which led on from the portrait. When Peter Blake got involved, the portrait idea grew. We had the big list of heroes: maybe they could all be in the crowd at the presentation!

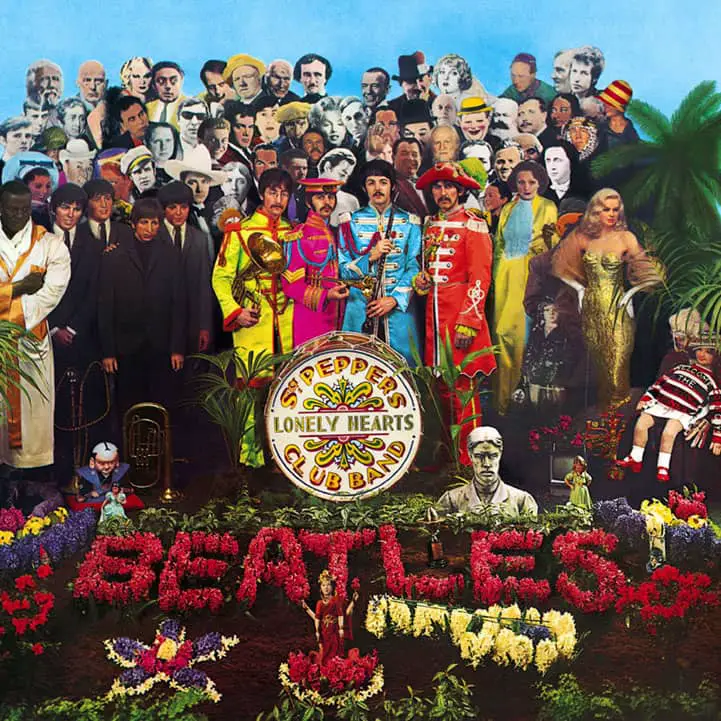

The widely-imitated artwork, directed by Robert Fraser and designed by Peter Blake and his wife Jann Haworth, saw The Beatles positioned beneath a collage of famous names, standing among a floral display and behind the iconic Sgt Pepper drum – painted by fairground artist Joe Ephgrave.

Among the figures in the cover’s background collage were Aleister Crowley, Mae West, Carl Jung, Edgar Allen Poe, Bob Dylan, Stuart Sutcliffe, Aldous Huxley, Marilyn Monroe, Laurel and Hardy, Karl Marx, Oscar Wilde, Lewis Carroll, Albert Einstein, Marlene Deitrich and Diana Dors.

I asked them to make lists of people they’d most like to have in the audience at this imaginary concert. John’s was interesting because it included Jesus and Ghandi and, more cynically, Hitler. But this was just a few months after the US furor about his ‘Jesus’ statement, so they were left out. George’s list was all gurus. Ringo said, ‘Whatever the others say is fine by me’, because he didn’t really want to be bothered. Robert Fraser and I also made lists. We then got all the photographs together and had life-size cut-outs made onto hardboard.

Some of the figures were chosen by the album’s art director, gallery owner Robert Fraser.

The other part of my concept was to get everyone in the group to mention their heroes. You’d have a portrait of someone and around him would be all the little portraits of Brando, James Dean, and Indian guru, whoever you were into. Or rather the alter ego’s heroes. There’d be HG Wells and Johnny Weissmuller, Issy Bonn and all those people, and Burroughs would have been a suggestion probably from Robert and there were a few kind of LA guys that Robert had slipped in. He’d slip in people that we didn’t even know but we didn’t mind, it was the spirit of the thing. Those ideas developed and combined, so that instead of a mayoral presentation it became that famous cover.

Groovy Bob, Harriet Vyner

Neither Blake nor Haworth were drug users, putting them at odds with The Beatles, Fraser and much of Swinging London. Furthermore, they worked on the cover without having heard the completed album.

They [McCartney and Fraser] happened to come to the studio one night and were just on a trip, you know, they were seeing things that weren’t there – seeing colours and seeing things that simply weren’t there and persuading me that I had to do it! You know, saying, ‘Look, you’ve got to, you’re not living a full life unless you experience these things.’ I don’t know how I ever insisted on not doing it, because the pressure to participate was enormous, but I just never did, you know. Which I am not particularly proud of. I mean, I am glad I didn’t, but it would have been a great deal easier to. The idea of that amount of responsibility being taken away from you. I never mind getting drunk and I never mind losing that sense, but LSD did frighten me. That was probably a good thing.

Groovy Bob, Harriet Vyner

Although Blake and Haworth worked diligently on the cover concept, there remained some initial uncertainty as to whether it would come to fruition.

The cover that The Fool had done looked quite groovy and I don’t think George was too happy about abandoning it. I thought it was fun, quite entertaining, and if you’d heard the music, which I hadn’t, probably apt, in terms of the psychedelia. I don’t think the final Sgt Pepper cover is at all psychedelic. Neither Peter nor I had anything to do with drugs and it was very much a continuum of both his work and mine.We didn’t know until quite late on whether they would actually use our cover or not. We went over to EMI and were shown this cover and the three of us were discussing what might be possible, rather briefly. Then Paul came over to the Chiswick flat one evening and discussed it further and really progressed it.

Groovy Bob, Harriet Vyner

A visit by the two artists to EMI Studios at Abbey Road led to further progress on the concept, although it also laid bare the cultural differences between them and The Beatles.

A very strange scene met us the first time we went over to the studio. The Beatles were recording, and their ‘court’ of Marianne Faithfull and all these weird spaced-out people sat around the walls. Peter and I were probably the only people who were stone-cold sober. It was really funny, two very upright people doing this psychedelia.Paul played us the tape of Sgt Pepper, which was still being worked on, and Peter thought the idea of making a Lonely Hearts Club would be interesting, a group of people with The Beatles in front. Early in the Sixties Peter had done some things, cutting out Victorian heads, engravings, sticking them down, then doing a circus act in front of that. He maintained at that time that Paolozzi nicked that idea from him, the collage effect of people and things, dissimilar but in the same environment.

The part that’s very much my own was that I always hated lettering on things. I loved the idea that lettering could be an integral part, and I was into fairground lettering at the time. So I thought it would be nice to have a real object with lettering on it, instead of lettering the cover. So I thought about the drum, then about the civic lettering that was around at that time. We pointed out to Paul the Hammersmith lettering: You could do it like that.

What I wanted was that very tight, little ice plants, a very tight floral near-to-the-ground thing. I discussed all this on the phone with the florists. Then they turned up with all these dumb plants – hyacinths. And then only a quarter of what we needed to cover the whole thing. After all these instructions. At least when they set it out you could read the word ‘Beatles’, but it was very much a failure in terms of the original concept.

The other part I felt very strongly about was that when you went from the front, you wanted to have that connecting point of 3D things that bled into the 2D things, as we were not doing it as artwork. This bothered Peter a lot later on, because it was so retouched, so messed about, the photograph, it ended up looking like artwork, a collage done on paper, rather than a set that was built.

Madame Tussaud’s were very generous, lending us some figures, and then The Beatles were going to be in front of the crowd, and I put some of my figures in, and that blended the 3D world into the 2D world.

Groovy Bob, Harriet Vyner

Ah yes Avery Road my fav Beatles album.lol

I read a quote from George once where he stated for him making Sgt Peppers was not a pleasant experience. It was Paul’s baby and he only allowed the others to contribute as he saw fit.

Personally I prefer the White Album and Revolver and Abbey Road being my fav Beatles album.

I’m sure you have Martin on camera or tape saying this correct? All I’ve ever seen Sir George speak about was how he took two “incomplete” songs given to him from Paul and John where he worked out the basic arrangement which eventually became Day In The Life.

Trixie is referring to George Harrison who indeed stated he was not really “into” that album when recording it.

George Martin didn’t weld the two parts of “….Life”. John and Paul did. Then Paul and George M. worked out the arrangements.

Beatles Bible states that “Sgt. Pepper” was issued (in the UK) on 1st June 1967. I am certain it was issued on 26th May 1967. The Beatle Monthly magazine issued on 1st June 1967 indicates that the release had already happened and the album entered the UK album chart at No. 1 on a chart published 1st June 1967, both signifying that the release must be before 1st June. Interestingly, the 2017 50th anniversary remix/reissue was released on 26th May 2017, which ties in exactly with what I think/remember as being the original release date in 1967.

Game changer. I think John outshone Paul on this one. The most creative song (in my opinion) was George’s song, though. That song changed me.

I would like to know if you intend to take into account the information that appears in the 50th anniversary deluxe edition of “Sgt Pepper”. There are lots of new and interesting things. For example, John’s bass in “Fixing a Hole,” George’s mellotron on “Strawberry …” or Paul and Ringo drumming on “Good Morning …”, which explains that full sound. However, there are also contradictions or omissions. For example, in “Strawberry …” they do not say who plays the piano or percussion. In “A Day in the Life” it says that John plays piano, but it does not specify if it only refers to the final chord, because in the line-up it does not specify who they played in that chord. In “Being the benefit …” they omit John’s piano and Lowery, but they talk about a Martin mellotron. What do you think?

Paul overdubbed bass on “Fixing a Hole” and AFAIK, John and George both played guitars on “Good Morning, Good Morning” with Paul playing the guitar solo as well as bass and the double drums with Ringo, just as you mentioned.

A number of sources (Wikipedia being one, so tread lightly) say that the album was going to be called Dr. Pepper’s LHCB, but wasn’t because of the soda in the US. If true, that puts Macca’s name origin story in a different light.

On Sgt Pepper, (on the CD) shouldn’t the “hidden track” be somehow hidden instead of tagged on the end of A Day In The Life? Like with a signal that the CD is over and just ends, unless you hit the skip button to go to the final track before it stops (if you want to hear it). I mean it would be a little more “in the day” that way.

Beatles fandom myth begins…”Sgt. Peppers is the first concept album”. Myth dispelled by actual Beatle John, who says, ” besides the opening song leading into the next song, you could take any song off this album and put it onto any of our albums”. Of course, as we all know, a concept album is when all songs were written with a predetermined theme each relating to another. When I’m 64 was written by Paul when he was 16. Benefit for Mr.Kite was written by John by essentially rewriting what he had read off an antique poster.

Who keeps adding musician names to the list and why?!?

Joe, the site creator/moderator does as he becomes aware of more information.

Pretty simple, isn’t it?!?

In Part 4 above, George Harrison is quoted as saying, “I’d just got back from India, and my heart was still out there. After what had happened in 1966, everything else seemed like hard work. It was a job, like doing something I didn’t really want to do, and I was losing interest in being ‘fab’ at that point.”

What was it that had happened in 1966??

Brian Epstein died, then they went on their transformational trip to India. I think that was the order of things, though I could be wrong. They were all grieving Epstein’s death, and people handle grief in different ways. Paul poured himself into work, and I guess George didn’t feel like it. He did come up with probably the most meaningful song on the album, though, Within You, Without You, obviously inspired by his time in India, and, to an extent, his grief.

As for the Personnel section: Paul: vocals, … and drums (Good Morning Good Morning). First time for Paul on drums on the Beatles album. By the way, does anyone know if Paul played one of Ringo’s drum kits here?

From “Mad Magazine” when I was probably 11. I was nine when SPLHCB was released.

“Ringo, George, Paul and John, played a trick and put us on. Dropped a hint that Paul was dead as nails and rocketed their record sales”

I first heard Sergeant Pepper in about 1974 I think, I borrowed it from a friend at school when I would have been about 16. I was a Beatles fan by default almost, to people of my generation they were just there, and you expected them to come out with brilliant things. I was extremely disappointed by this album which I thought sounded muddy compared to other Beatles efforts. I had heard Penny Lane and Strawberry Fields by then, but the only songs from the album as such that I recognised were When I’m 64 and With a Little Help From My Friends, possibly only from covers, so the material was farily new to my ears. I still think that notwithstanding its brilliance it is questionable whether as a sum of its parts it equals other Beatles albums, before or after. There are only a couple of songs in my view on the album or released as singles that are good songs and are also as well arranged and produced as they could be, including Fixing a Hole and Within You Without You. There are other brilliant songs such as With a Little Help From My Friends, When I’m 64, Lucy in the Sky, Good Morning that are really to my ears let down by the arrangements. I would also include Penny Lane (is that clunky piano really that interesting?) and A Day in the Life (this is a pop group/rock band whatever, who let that orchestra in here, they’re ruining the song?!). And then there are items of what could just be whimsy such as Lovely Rita which is almost perfectly arranged and produced, and Getting Better, which in the absence of its arrangement performance and production would barely be a song at all, but which I think is one of the most brilliantly executed recordings they ever produced. So coming to it some years after it was issued it struck me as patchy, and still does.

I don’t blame EMI for rejecting John’s brash suggestion of putting Hitler on the cover, because it would have been very offensive to Germans and survivors of the Nazi regime. According to Horst Fascher, John would often greet the audiences at the clubs in Hamburg with a Heil Hitler and give the Nazi salute, pull out a black comb and pretend it was a moustache, so that he could look like Hitler.

I’m surprised that John didn’t get arrested by the German authorities or put in a Hamburg prison, because giving the Nazi salute or chanting “Sieg Heil” is a criminal offence in Germany, according to Strafgesetzbuch section 86a.

As for the Personnel section: Paul: vocals, … and drums (Good Morning Good Morning). First time for Paul on drums on the Beatles album. By the way, does anyone know if Paul played one of Ringo’s drum kits here?

I have seen a photo where Ringo is playing his drum kit at a studio session and a clean-shaven Paul is standing up with some drumsticks, presumably to play on the floor tom.

The second drum part in question on “GM, GM” could well have been Ringo and Paul collaborating on double drumming and to clarify things, Paul’s part would, logically, have been intended to augment, not replace, Ringo’s drumming – an earlier instance occurred on the recording of “Yes it is” when Paul overdubbed a cymbal, again to augment Ringo’s drums.

Sorry, but for anyone who puts SPLHCB down in any way (notwithstanding comparing that which preceeded or followed) basically you need to go get some new ears. Any of the more recent masterings show that the main driver (Sir Paul) steered the Beatle ship at this period. The guy was basically on fire from 66 onwards when the touring ceased

I always wanted to know WHY Paul turned his back to the camera for the back cover photo? And why would they use that photo for the album? It is so odd a choice. It practically invites the “Paul is dead” crowd to notice and interpret.

I suppose we’ll never know.

I remember hearing that it was Mal Evans standing in for Paul on that back cover shot – forget why, but McCartney wasn’t at the shoot (separate one from the cover)

I never heard the Mal stand in story. Makes sense if it’s true. Thanks for sharing.

Cheers!

Mal Evans standing in for Paul? In his biography on this website Joe describes Mal as “tall and burley.” Paul was hardly tall and burly. Couldn’t be Mal unless someone manipulated the photo to make Mal look more like Paul in stature.

That’s true. Mal Evans was 6 feet 3 inches tall.

Paul is 5 feet 10 inches. Unless it’s a cardboard cutout of Paul’s back as a subtle allusion to the front cover? Someone should ask Paul!

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2023/aug/14/photo-that-solves-sgt-pepper-mccartney-mystery-up-for-auction

“It had long been rumoured that Paul McCartney was not at the Sgt Pepper’s sleeve photo shoot because the back of the album only showed him from behind. This image showed the side of his face which would prove that he was indeed there on the day.”

So this photo shone on The Guardian website from Aug 14 2023 proves McCartney was present at the Pepper photo-shoot for the back cover. But the question remains… Why turn your back, Paul?

@ Neall Calvert

You asked, “What was it that had happened in 1966??” to make George lose so much enthusiasm for carrying on as a Beatle like before.

I think he is referring to two things in particular.

First, during their world tour, they had a horrible experience in the Philippines. They had been invited to visit the palace of the ruthless dictator of the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos, who was ruling the country under martial law. The Beatles declined the invitation because it was scheduled for one of their rare days-off and they desperately wanted a break to relax and have a rest. The television news was broadcasting what was supposed to be live coverage of President Marcos and his loathesome, kleptocratic wife, Imelda, “honouring” their guests with an official reception. When The Beatles failed to appear, the dictator felt humiliated. He made an angry announcement to the effect that The Beatles were depraved Western degenerates who had been sent to the Philippines to corrupt the nation’s youth. He ordered that they be deported immediately.

Not only did The Beatles have to make their own way to the airport without any security protection but the local police actively encouraged the public to give the Fabs a hard time. George got the worst of it and was beaten up pretty roughly. He had a black eye to show for it. The authorities also stole all of the money which The Beatles had earned for their work.

Years later, when the rest of the world had found out what a nasty piece of work Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos really were, George stated that, looking back, he was quite proud that he and The Beatles were one of the few people who had stood up to these thoroughly nasty, unpleasant people while everybody else in the political sphere bowed and scraped to them.

Well said, George!

But it was still a terrifying experience for him at the time.

If anything, it got even worse when they proceeded from the Philippines to the USA for what proved to be their final American tour. John’s “Jesus Christ” statement from months before had suddenly been made into a major controversy by influencers in the American “Bible Belt”. They found that the American press corps had turned against them. The press conferences had become aggressive and confrontational. This was a stark contrast to the previous routine where the engagements with the press were characterised by witty entertainment and good-humoured exchanges.

Lunatic fringes such as the KKK were stoking the fires and numerous death threats were taken very seriously by local police departments. At one point, somebody through a firecracker onto the stage while The Beatles were performing. When they heard it exploding, every one of them looked around to see if one of them had been shot.

No kidding.

From George’s point of view, the tour was a living hell and at the end of it, he said, “That’s it! I’m never going to go through this again. I’m finished with touring.”

After that tour, The Beatles took their first extended break for years. George went off to India and acquired an entirely new perspective on his life and it never left him. That was the frame of mind in which he returned to England in late 1966 to start work on what became the Sgt. Pepper project. He had become convinced that there were far more important things in his life than simply being “Beatle George.”