The Beatles’ Get Back project was the group’s attempt to return to their roots. It initially saw them rehearsing and recording songs for a television special and live performance at Twickenham Film Studios, before sessions moved to the Apple HQ later in January 1969.

Motivation was low within the group. Paul McCartney aside, there was little enthusiasm for a mooted live appearance. The Beatles were still exhausted after the lengthy sessions for the White Album, and the presence of film cameras during the rehearsals created a further strain.

Although not all the January 1969 sessions were tense, The Beatles were often at odds with one another. George Harrison found McCartney bossy and domineering, and John Lennon was addicted to heroin and unwilling to be parted from Yoko Ono.

In a nutshell, Paul wanted to make – it was time for another Beatle movie or something, and Paul wanted us to go on the road or do something. As usual, George and I were going, ‘Oh, we don’t want to do it, f**k,’ and all that. He set it up and there was all discussions about where to go and all that. I would just tag along and I had Yoko by then. I didn’t even give a s**t about anything. I was stoned all the time, too, on H etc. And I just didn’t give a s**t. And nobody did, you know…Paul had this idea that we were going to rehearse or… see it all was more like Simon and Garfunkel, like looking for perfection all the time. And so he has these ideas that we’ll rehearse and then make the album. And of course we’re lazy f*****s and we’ve been playing for twenty years, for f**k’s sake, we’re grown men, we’re not going to sit around rehearsing. I’m not, anyway. And we couldn’t get into it. And we put down a few tracks and nobody was in it at all. It was a dreadful, dreadful feeling in Twickenham Studio, and being filmed all the time. I just wanted them to go away, and we’d be there, eight in the morning. You couldn’t make music at eight in the morning or ten or whatever it was, in a strange place with people filming you and colored lights.

Lennon Remembers, Jann S Wenner

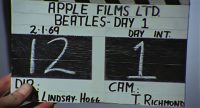

The project was initially to have been a live show of White Album songs, but The Beatles decided instead to write and rehearse 14 new songs in just two weeks. The rehearsals took place in Stage 1 at Twickenham Film Studios, which had been hired until the end of May by Denis O’Dell, head of Apple Films, for The Magic Christian, starring Ringo Starr and Peter Sellers.

The initial plan was to also film the TV special at Stage 1, with a dress rehearsal on 18 January, and live shows on 19 and 20 January. Starr was due to begin work on The Magic Christian on the 24th.

George Harrison walked out of the group on 10 January 1969, and the plans for the television special were abandoned. He agreed to rejoin The Beatles only if they moved from Twickenham to their new recording studio in the basement of their Apple HQ in London’s Savile Row. This they did from 21 January, in the process dropping plans for a live concert.

Because the audio needed to be good enough for potential use in a film or television programme, it was recorded on Nagra reel-to-reel ¼” mono tape machines. Two were used, one for camera A and one for camera B. They could capture only 16 minutes on a tape, and so the two machines were started at different intervals.

As a result, the Get Back sessions were extensively bootlegged, providing a fascinating insight into The Beatles’ working practices. A vast number of songs were performed by The Beatles during January 1969, many of which never saw light of day in an official capacity, though works from Abbey Road and their solo albums did emerge, in addition to the Let It Be songs.

They also jammed a great deal; sometimes at length and without much artistic merit. The better attempts were included in the Let It Be film and the 2021 Get Back documentary. The Beatles, whether out of boredom or desperation, played tunes ranging from nursery rhymes (‘Baa Baa Black Sheep’) and rock ‘n’ roll classics (‘All Shook Up’) to pre-‘Love Me Do’ original compositions and improvised songs (the unreleased ‘Suzy Parker’).

The Get Back rehearsals followed a Monday to Friday schedule, and each day started between 11am and 1pm. On this first day the group arrived at Twickenham at 11am, apart from Paul McCartney who was delayed on public transport, and arrived at 12.30pm.

This first day officially began at around 9.30am, however, with director Michael Lindsay-Hogg filming as Mal Evans and Kevin Harrington set up The Beatles’ equipment onto stage one before the group began playing. The shots would eventually be used for the opening sequence of the Let It Be film, and the Get Back documentary.

Watching the first day was Shyamsunder Das, a friend of George Harrison. “Who’s that little old man?” John Lennon asked. “Clean though,” added Paul McCartney, a reference to Wilfrid Brambell in A Hard Day’s Night.

The Beatles spent much of their time working on three songs: ‘Don’t Let Me Down’, ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’, and ‘Two Of Us’.

Performances of ‘Don’t Let Me Down’, ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’, ‘Johnny B Goode’, ‘Two Of Us’, ‘Quinn The Eskimo (The Mighty Quinn)’, and ‘I Shall Be Released’ from this day appeared in part one of the 2021 documentary Get Back.

The full list of songs played on this day, including fragments and off-the-cuff, unpublished songs with presumed titles:

- ‘Don’t Let Me Down’ (15 versions)

- ‘All Things Must Pass’ (two versions)

- ‘Dig A Pony’

- ‘Let It Down’ (Harrison; two versions)

- ‘Brown Eyed Handsome Man’ (Chuck Berry)

- ‘Johnny B Goode’ (Chuck Berry)

- ‘A Case Of The Blues’ (Lennon)

- ‘Child Of Nature’ (Lennon)

- ‘Revolution’

- ‘I Shall Be Released’ (Bob Dylan)

- ‘Sun King’ (five versions)

- ‘Mailman, Bring Me No More Blues’ (Buddy Holly)

- ‘Speak To Me’ (Jackie Lomax)

- ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’ (20 versions)

- ‘Quinn The Eskimo (The Mighty Quinn)’ (Bob Dylan)

- ‘Well… Alright’ (Buddy Holly)

- ‘Two Of Us’ (nine versions)

- ‘Everybody Got Song’* (Lennon)

- ‘The Teacher Was A-Lookin”* (group jam)

- ‘We’re Goin’ Home’* (group jam)

- ‘It’s Good To See The Folks Back Home’* (McCartney)

* presumed title.

View the complete list of songs played during the January 1969 Get Back/Let It Be sessions.

Lennon and Harrison were the first to arrive, the former with his then-girlfriend Yoko Ono. As they tuned their guitars, the musicians played snippets of ‘Don’t Let Me Down’ and ‘All Things Must Pass’. Both attempted to play along with each others’ songs, and were joined by a recently-arrived Ringo Starr on drums during a version of Don’t Let Me Down.

Lennon then played a solo version of ‘Dig A Pony’, before improvising a song known as Everybody Got Song. Harrison put forward another, ‘Let It Down’, which was eventually recorded for the All Things Must Pass triple album.

Lennon improvised a guitar instrumental and sang two verses of Chuck Berry’s ‘Brown-Eyed Handsome Man’, joined by Harrison in places. They then turned to ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’, which at this stage lacked McCartney’s contributions. Lennon’s part was based on a 1968 home recording known as ‘Everybody Had A Hard Year’. He also played through an unfinished song titled ‘A Case Of The Blues’, which was mostly instrumental.

Lennon’s ‘Child Of Nature’ – later rewritten as ‘Jealous Guy’ – was introduced on this day as ‘On The Road To Marrakesh’. He sang two verses, with Harrison joining in several places. Its presence here served to highlight the dry spell Lennon was undergoing as a songwriter; the song had been written in India more than six months previously.

Snippets of ‘Revolution’ and Bob Dylan’s ‘I Shall Be Released’ followed, and a new unfinished Lennon song, ‘Sun King’. During the performance, which contains elements of ‘Don’t Let Me Down’, McCartney arrived at Twickenham and began playing along.

During the day two Bob Dylan songs and two by Buddy Holly were attempted by the group, along with Chuck Berry’s ‘Brown-Eyed Handsome Man’. Holly’s ‘Mailman, Give Me No More Blues’ wasn’t the take eventually issued on Anthology 3; that was recorded on 29 January.

With all four Beatles finally in the same room, they discussed the purposes of the Get Back project. Lennon expressed dissatisfaction with the large size of the sound stage, and with having cameras present during these early rehearsals, but McCartney defended the set-up. Their words appear to indicate that that the intention at this time was to film a television special inside Twickenham with an invited audience.

McCartney took the vocal lead on several versions of ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’, teaching the others the song’s structure as he went. The Beatles spent some time working on the arrangement.

In the afternoon Harrison led Starr through a cover version of Jackie Lomax’s ‘Speak To Me’, before work continued on ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’ – at this stage The Beatles’ most complete song. Numerous run-throughs took place as the group continued shaping it, breaking off for discussions in between.

The Beatles then turned their attentions back to ‘Don’t Let Me Down’, and discussed possible instrumentation. At this stage they were considering bringing in a keyboard player, with Nicky Hopkins’ name mentioned.

During a break for sandwiches Harrison played the Buddy Holly song ‘Well… Alright’, followed by another version of ‘All Things Must Pass’.

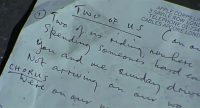

Instead of working on Harrison’s song, The Beatles moved on to McCartney’s ‘Two Of Us’. A lengthy rehearsal took place, with McCartney teaching the rest of the group the chord and time signature changes. Evidently The Beatles weren’t familiar with it yet, although they would play it a great many more times during the month.

In a break from ‘Two Of Us’, The Beatles improvised a song known as ‘It’s Good To See The Folks Back Home’, led by McCartney. They returned to ‘Two Of Us’ before the day’s work came to a close.

John: “And of course we’re lazy f*****s and we’ve been playing for twenty years, for f**k’s sake, we’re grown men, we’re not going to sit around rehearsing.” Playing for 20 years? Is that a joke or was Lennon really that high? He was only 30 years old when he said it.

Exaggerating obviously, and “20 years” has more bite than 10 or 12.

So true. Although being high doesn’t help.

Hahaha!

The “Let It Be” / “Get Back” sessions were in January 1969. McCartney & Lennon met in 1957, as teenagers. So they’d been playing together for 12 years, give or take, in 1969. But Lennon was a member of The Quarymen when they met. Both he and McCartney must have been playing for more than a year before they started playing in public together. It wouldn’t be wildly improbable that they’d played individually for 3 or more years before being in a band together. 15 years of actually playing becomes 20 hyperbolic years in a heartbeat. Ask any 30-year-old how long they’ve been doing something they started at age 15.

I say the following as a fan since 1964 of John Lennon. I’m somebody who has his picture on the wall of my cubicle to tell my co-workers where I stand on the great issues of the day. (The great issues of the day in my opinion are creative freedom and plunging deep into the soul to see what’s there; on these issues, I’m right there with John Lennon.) OK. That said, I would now like to paraphrase something said long ago by some dead writer about another writer – I think it was Mary McCarthy talking about Lillian Hellman – “Every word she wrote was a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the.'” That’s how I sometimes feel about the first big interview John Lennon did for Rolling Stone, which is obviously STILL being hauled out as a valid source. It’s not. It’s not a valid source. I’ll say it again: It’s not a valid source. He lies in it, he exaggerates in it, he basically commits libel against Paul McCartney at every opportunity, and if I had been Paul McCartney’s lawyer in 1971 when the interview was republished as a book and appeared on every drugstore book rack in the country, I would have said to my client, “Let’s sue this guy. We can collect at least $100 million for the damage he’s done to your reputation. He has done permanent damage to you and that’s what libel laws exist for.” When a quote from the interview is hauled out, as on this Web page, it should always be couched in appropriate language, i.e., “Bear in mind John Lennon was an extremely angry and unstable person at the time of this interview, more interested in settling scores than in speaking the truth.” The quote should be thusly couched because a whole lot of young folks are coming along reading the B.S. that guy spewed in that interview and saying, “Oh, hmmm, yes, John Lennon said it, it must be true.”

Looks like working in your cubicle and staring at John every working day has aroused judicial fantasies.

You should have become a lawyer like in your fantasy and represented Paul in a lawsuit against John. That’s what a real John Lennon “fan” would do!

The RS interviews will always be a valid source for those wanting to know what Lennon was thinking and feeling at the time.

It’s not 1971 anymore.

Paul got over it. Why can’t you?

I actually am “over it,” to whatever extent “getting over it” is an applicable concept here. I doubt that Paul actually got over it. My note is aimed at kids under the age of, say, 18, who have never heard of the Rolling Stone interview before, don’t know the deep background, stumbled on this Website as research for doing a paper or presentation for high school, and think that the interview represents reality. I like the idea of telling them “No it’s not.”

What you are implying is that teenagers under the age of 18 who visit this site and who haven’t read the RS interviews needs to be guided by your opinion as if you have priveleged information on the subject.

A teenager can read the RS interviews and make their own judgements without outside help.

I am not implying that people under 18 who visit this site and haven’t read the Rolling Stone interview need to be guided by my opinion. I am not remotely suggesting that. Nor am I suggesting that I have privileged information. I am offering my opinion/assessment/input, in strong terms to make sure that my opinion is clear, on the capacity for bald-faced lying of John Lennon circa 1970-71. Whether they find my input useful is entirely up to them. Judging from the worshipful attitude many young people today have toward John Lennon (I base this on conversations at Burning Man, from reading various Comments sections at YouTube, etc.), a significant percentage of them find his word to be gospel truth.

Good luck in trying to change the “worshipful attitude many young people today have toward John Lennon”! If Burning Man and You Tube are the sources of your assessment of “young people today” your opinion of today’s youth is shortsighted. There are a lot of young people today who despise John Lennon for his music and his political stance. Today’s youth who appreciate John Lennon do so because of his musical legacy, not the RS interviews. But then again you don’t comment about music.

Thank you for the good luck wishes. By the way, I do not base my assessment of young people today only on Burning Man and YouTube, as my previous comment clearly states.

By the way, your June 21 comment clearly states that you only mention Burning Man and You Tube as sources.

I for one am grateful that most people have gotten over the”let’s blame Paul for everything” mindset.He and his demanding ways and what not. My opinion based on what I’ve read and seen Is that Paul was doing one thing: trying to keep the band together Hewas the only one who cared. From the inception of the Beatles until the day they broke up, Paul loved that band the most, and he was desperately trying to save it.

As far as the RSinterview , John did call Paul’s music garbage . He did say it and it hurt Paul terfibly.

I do know Paul was not blameless , and he probably was bossy trying to take on leadership of the band( which I think he already had).

But Paul is not the one who gave up his best mate for a woman and a drug addiction.

Thank you Beatles Bible for providing what appears to Be an accurate, unbiased account of what happened.

Why has this movie been effectively airbrushed from history? You cannot buy it or even see it on television anymore.

Olivia Harrison prevented the re-release of the Let It Be movie.

Later in the same Rolling Stone interview Lennon said this:

“All our buddies that worked for us for fifty years were all just living and drinking and eating like f*in’ Rome, and I suddenly realized it and – I said to you – ‘we’re losing money at such a rate that we would have been broke, really broke.'”

Obviously “fifty years” here, like “twenty years” before, was just an exaggeration meant to convey “a long time.”